3.1 The Alphabet

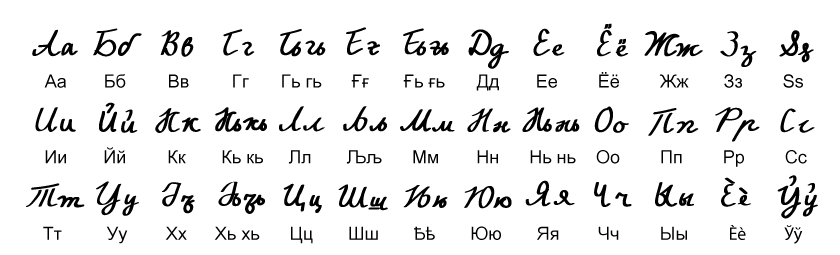

Novegradian uses a modified form of the Cyrillic alphabet with 35 letters, as shown in the following table. Due to many centuries of contact, the letters and spelling used are somewhat similar to Russian. Alongside each character are the letter’s standard transliteration (as used in this document), primary phonetic value, and name.

| Letter | IPA | Translit. |

Name

(IPA) |

Name

(Translit.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| А а | a | a | a | á |

| Б б | b | b | bɛ | bé |

| В в | β, w | v | βɛ | vé |

| Г г | g | g | gʲɛ | gé |

| Гь гь | ɟ | gj | ɟa | gjá |

| Ғ ғ | ɣ | ğ | jɛ | ğé |

| Ғь ғь | ʝ | ğj | ʝa | ğjá |

| Д д | d | d | dʲɛ | dé |

| Е е | je, e | ie, e | jejɛ | iéie |

| Ё ё | jo | io | jɔ | ió |

| Ж ж | zʲ | ź | zʲa | źá |

| З з | z | z | zʲɛ | zé |

| Ѕ ѕ | dz | dz | dzɛ | dzé |

| И и | i | i | i | í |

| Й й | j | i, j | i krasko | i krásko |

| К к | k | k | ka | ká |

| Кь кь | c | kj | ca | kjá |

| Л л | l | l | lʲɛ | lé |

| Љ љ | ɫ | ł | ɫa | łá |

| М м | m | m | jɛm | iém |

| Н н | n | n | jɛn | ién |

| Нь нь | ɲ | nj | jɛɲ | iénj |

| О о | o | o | uo | ó |

| П п | p | p | pɛ | pé |

| Р р | r | r | ra | rá |

| С с | s | s | sʲɛ | sé |

| Т т | t | t | tʲɛ | té |

| У у | u | u | u | ú |

| Х х | x | h | xʲɛ | hé |

| Хь хь | ç | hj | ça | hjá |

| Ц ц | ts | c | tsɛ | cé |

| Ш ш | sʲ | ś | sʲa | śá |

| Ѣ ѣ | æ | ě | jate | iáte |

| Ю ю | ju | iu | ju | iú |

| Я я | ja | ia | ja | iá |

The digraphs гь, ғь, кь, нь, and хь are considered single letters, and in dictionaries and other alphabetical listings are ordered after the non-palatal consonant they are based on. On vertical signs they are always grouped together, and in crosswords they fit into a single box. However, although they are single letters, they are composed of two distinct glyphs, meaning they have two majuscule forms: the ‘upper case’ ГЬ ҒЬ КЬ НЬ ХЬ in all-capital texts or headlines, and ‘title case’ Гь Ғь Кь Нь Хь when at the beginning of a word.

3.2 Extra Letters

In addition to the above, there are a number of extra letters not included in the alphabet, but often used to represent certain sounds in loanwords.

| Letter | IPA | Translit. |

Name

(IPA) |

Name

(Translit.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ч ч | tʃ | č | tʃa | čá |

| Ы ы | ɨ | y | irɨ | irý |

| Ѐ ѐ | e | e | jɛ twirdo | ié tuírdo |

| Ў ў | w | w | u krasko | ú krásko |

The last, Ў, is a variant form of У representing only the semivowel /w/. It is very rarely written unless sort sort of confusion could result (i.e., whether it is a diphthong or two syllables). It is also used in the very few word-initial clusters that begin with /w/. When the sequence /wu/ appears, u krásko is always used, as in дўудешитех dwudéśiteh “of twenty”.

Ѐ (whose name literally means “hard E” or “fixed E”) is a variant of Е, though its function is mostly lexical. It appears on the end of indeclinable nouns that end in /e/ (mostly foreign loan words, such as ковѐ kóve “coffee”) to clearly differentiate them from fourth declension nouns and indicate that the /e/ is in fact part of the noun stem. In speech the final -е of fourth declension nouns frequently drops, while final -ѐ can never be dropped under any circumstances. Compare саке sáke “bough” with сакѐ sáke “sake (alcohol)”. Note that while “Е” is called “ее” iéie in Novegradian, Ѐ is always called “е туирдо” ié tuírdo, never *iéie tuírdo.

When ordering, Ч and Ы are placed at the end of the alphabet, after Я. Ў is mixed among У and Ѐ among Е, as they are considered variants forms.

3.3 Spelling

Novegradian has a fairly regular spelling system, where the one letter - one phoneme ideal is for the most part maintained. However, there are a number of spelling rules that must be noted.

Voicing assimilation at the edges of morphemes is rarely indicated; to this extent Novegradian orthography may be considered as following the ‘morphological principle’ rather than the ‘phonetic principle’. Similarly, word-final devoicing is usually not indicated: ниг níg “books (gen.pl)” [ˈnʲik].

Й represents /j/ post-vocalically and pre-consonantally. As such, it is generally only used to represent the sound as the second element of a diphthong (ай ai), or as the first element of a cluster (йсе jse). The only exception is the sequence йи, which is used to represent the sequence /ji/ word-initially, though this is very rare. When the /j/ is followed by another vowel, the ‘iotafied’ letters Я Ѣ Е Ё Ю are used: ая aia.

The letters Е and Ѣ are always considered iotafied. At the beginning of a word and after another vowel they are pronounced [je jæ], and when stressed after a dental or velar consonant they palatalize the consonant as described earlier. Only after the non-palatalizable consonants, such as the labials, are the stressed forms just pronounced /e æ/ without any palatal element.

У is used to represent both the vowel /u/ and the semivowel /w/, including in diphthongs. Normally there is little confusion as to which pronunciation is intended, but if there is, the variant form Ў may be used to represent /w/. This is most common in clusters or before е or ѣ: ўсе wse, усе use; ўе we, уе uie.

Ғ at the end of a word is pronounced /j/, as though that were its unvoiced counterpart. However, there are a number of words where this /ɣ/ [j] is actually spelled <й> in unsuffixed forms. Which words use this alternation and which always use Ғ must be memorized.

Ѣ is pronounced [æ] when stressed and [i] when unstressed. While this letter is generally used to represent both, in many non-changing words, particularly prepositions, variant spellings with both ѣ and и may be seen if the vowel is unstressed, such as намѣстѣ/намѣсти “instead”. Generally the spellings with ѣ are more formal or archaic than those with и.

When the sequences /je/ or /jæ/ appear after a consonant, they are generally spelt ие/иѣ, not е/ѣ or йе/йѣ: обиеме obiéme. All other sequences of /j/+vowel are written with just an iotafied vowel: шѣмя śěmiá. For the purposes of romanization /j/ will generally be represented with “i”; “j” will only be used for word-intial /j/ before a consonant and for /j/ in the sequences /ij ji/ (e.g., цервение cervénije). The letter “j” in kj, gj, hj, ğj, and nj represents the palatal series of consonants.

When an intervocalic voiced consonant occurs that was historically an unvoiced geminate, it is written using the unvoiced followed by the voiced form of the consonant: сутда sutdá “floor, storey” (originally /sut.ˈta/, now /su.ˈda/). The one exception is /zʲ/, which is written шз: Рошзия Rośzíja “Russia” (originally /ros.ˈsʲi.ja/, now /ro.ˈzʲi.ja/).

The foreign sequence /dʒ/ is typically represented as дч dč, not as дж as in Russian or other languages using Cyrillic. This can be seen in native words such as кудчом kudčóm, the genitive plural of кучма kúčma “fur hat”, or in foreign terms such as the English name Дчордче Dčórdče “George”.

In addition to the above there are many instances of spellings that are simply irregular. There are two main sources of these spellings. The first consists of native words that have since undergone reduction or assimilation, or foreign loans whose spellings were never changed to more accurately reflect the “Novegradianized” pronunciation. Examples of the former include наступне nastúpne “next, following” (pronounced [nə.ˈstu.ne]) and росхирати roshiráti “expand” (pronounced [ro.ski.ˈra.tɪ]). Examples of the latter include ахтивне ahtívne “active, working” (pronounced [əx.ˈtʲi.ne]) and нводише nvodíśe “leader, commander” (pronounced [βo.ˈdʲi.sʲe]). Often two pronunciations exist for such words, one reflecting a more historically accurate pronunciation, and one reflecting the spelling: иске íske “lawsuit, legal action” can be pronounced [ˈis.ke], based on spelling, or [ˈjɛs.ke], the expected pronunciation given historical sound changes. The spelling of this particular word is actually an archaism, though ескати ieskáti “search for”, the word from which it was derived, has undergone the /i/ → /e/ shift.

Other words are spelt irregularly just because the Novegradian alphabet has no good way of spelling them regularly without resorting to measures considered ‘ugly’ by those that use it. An example is калеиша káleiśa “fishery” [ˈkal.ji.sʲə] where е is used to represent /j/ for little reason other than to avoid the uglier **калйиша or more repetitive **калииша. This may also be a carryover from the Old Novegradian habit of spelling /j/ as е, prior to the invention of the й glyph.

3.4 Foreign Loans

Most foreign loanwords entering Novegradian during or after the 20th century are spelt so as to more or less preserve the original pronunciation, although their pronunciation in Novegradian nevertheless may be vastly different.

Transcribing foreign phonemes into Novegradian tends to be more difficult, however. Foreign /f/ tends to become either /β/ (инвормася invormásia “information”) or /x/ (вотограхя votográhia “photograph”). It may also become /k/ when followed by /l/, the result of a later sound change /xl/ → /kl/: клоте klóte “fleet” (German Flotte). /θ/ and /ð/ become /t/ and /d/ respectively (теёлогя teiológia “theology”). Novegradian, generally not accepting of vowels in hiatus, will also add in semivowels where they did not originally exist (геёграхя geiográhia “geography”). /h/ becomes /x/, or sometimes at the beginning of a word, nothing.

Most other sounds are transcribed using methods similar to Russian’s. For example, the front rounded vowels /y/ and /ø/ become /ju/ and /jo/. A variant of the Palladiy system is used to transcribe Chinese, the Polivanov system for Japanese, and the Kontsevich system for Korean. Of course, the average Novegradian speaker has about as much luck figuring out Palladiy as the average English speaker has with Pinyin.

When foreign names begin with /e/ (with no inserted [j] as is mandatory in Novegradian), standard procedure is to insert an apostrophe in the spelling: ’Единбурге ’Edinbúrge “Edinburgh”. Since [j]-insertion in Novegradian is allophonic, this apostrophe generally does not change most people’s pronunciations unless they are trying to mimic the more ‘proper’ foreign pronunciation. This apostrophe is more of an orthographic device meant to keep transliteration as close to one-to-one as possible.

When transliterating from languages using the Latin alphabet, silent letters are usually dropped: Ренѐ Декарте René Dekárte “René Descartes”. However, no formal rule exists for cases for double letters, where the Latin-script letter isn't strictly silent; consequently variant spellings such as Сиетле Sijétle and Сиеттле Sijéttle “Seattle” may exist in more or less free variation.

3.5 Evolution of the Orthography

The evolution of the Novegradian orthography can be broadly divided into four historical stages: Slavonic, Early, Russified, and Modern.

The Slavonic period lasted from roughly the 10th century until the 14th century. During this time the written standard of Novegradian was essentially Old Church Slavonic, introduced to Novegrad by the Orthodox Church and considered the language of educated speech throughout Kievan Rus’. The written language of Novegrad, at least among the more educated classes, was essentially Novegradian vocabulary combined with Old Church Slavonic spelling, which included a number of letters for sounds that had disappeared in Novegradian and for transcribing Greek loanwords. As a result, misspellings were quite frequent, especially amongst the less educated, as many sounds could be represented by multiple letters. A common example of this is the confusion of when to use Ч and Ц, whose sounds had merged in early Novegradian; many people avoided the issue by writing Џ instead, halfway between the two characters! The Slavonic orthography also made heavy use of diacritics to indicate stress, palatalizations, and sometimes nothing at all, again the result of polytonic Greek orthography being imported wholesale into a language that had no need for it.

The Slavonic period did feature a few significant breaks from the Slavonic standard seen through the rest of Rus’, however. One curiosity is the almost complete interchangeability of the letters о/ъ and е/ь (with the exception of at the end of many masculine nouns in the nominative singular, where instead е/ъ were interchangeable).

The Early period lasted from roughly the 14th century until the 19th; its designation is therefore somewhat of a misnomer. In the 14th and 15th centuries, Novegrad, with its normal ties to the rest of Rus’ disturbed by the Mongols, began to develop a native, more suitable version of the Cyrillic alphabet. Many of the more useless Slavonic letters, such as the nasal vowels Ѧ and Ѫ, fell out of use. The yers (see Historical Phonology) Ъ and Ь dropped when silent or replaced with full vowels such as И, Е, or О, depending on how they were actually pronounced. However, the Slavonic standard of never allowing a word to end in a consonant remained, with one of the yers being required if the word did not end in a vowel. On the other hand, the redundant Greek letters remained in use, and in some cases even gained wider usage (as seen in spellings such as ψати psati for modern пизати pizáti “write” in dialects that dropped the first vowel). All diacritics except for the stress marker, palatalization marker (used to indicate the modern consonants кь, гь, нь, хь, ғь), and titlo (contraction marker) disappeared.

At the same time a number of quirky innovations began to appear as well. Novegradian continued to mark prevocalic /j/ using “iotation” (a ligature of an iota with the regular vowel, see chart below). However, where other languages using the Cyrillic alphabet adopted И (or И with the Greek “short” diacritic: Й), Novegradian adopted Е for postvocalic /j/. In addition, the letter Љ appeared out of a ligature of Л and Ъ, one of the most common environments for the new phoneme /ɫ/ to appear.

For much of the early period, there were relatively few standards in place defining set rules for what spellings were correct or incorrect. However, by the 17th century, conventions began to emerge. Breaking from its Greek origins, the letter w (omega) began to acquire a fixed use in the prefixes ot-/os- “from” and o- “at”. The sound /u/ could be conveyed in two different ways: by the digraph оѵ at the beginning of a word, or the ligature у anywhere else.

In the Russified period, lasting from the 19th century to 1918, a number of Russian orthographic conventions were forced onto the Novegradian language. The Civil Script formally replaced the old Slavonic typeset (although the Civil Script had fairly wide usage in Novegradian prior to then as well). Almost all of the remaining Greek letters disappeared except for І (representing iota) and, in a very small set of words, Ѵ (upsilon, known in Novegradian as ieźíca) and Ѳ (theta, or títa). All stress and palatalization diacritics were abolished, with Ь now being used to indicate Novegradian palatal consonants. Novegradian iotated vowels were brought in line with Russian’s, so that Ю, for example, now represented /ju/ instead of /jo/ as it had in Novegradian up to this point. Most uses of Е for indicating /j/ were replaced with Й, with the one exception of the series /ji/, which to this day is written еи. The letter Ў was formally added to represent consonantal /w/.

The Modern period began in 1918 with a proclamation of orthographic reform by the unofficial Bolshevik government, but was not fully implemented for over a decade. The foundations of the Russified orthography remained intact, the system having by then become firmly established. Several changes brought about by this reform parallel the reforms of Russian happening at the same time: the complete abandonment of Greek letters and silent yers. However, Ѣ remained, as unlike in Russian it still represented a distinct sound. The Russian letter Ё was adopted for /jo/, which under the Russian system could only be represented with the awkward sequence йо. The letter Ғ was introduced, for the first time distinguishing /ɣ/ from /g/ orthographically.

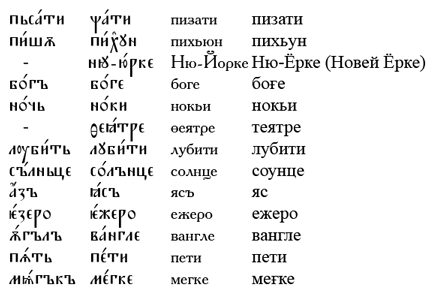

A few examples of various words in each spelling system are shown in the table below. The leftmost column is Slavonic-era spelling, followed by Early, then Russified, and finally Modern on the right.