23.1 Major Novegradian Dialects

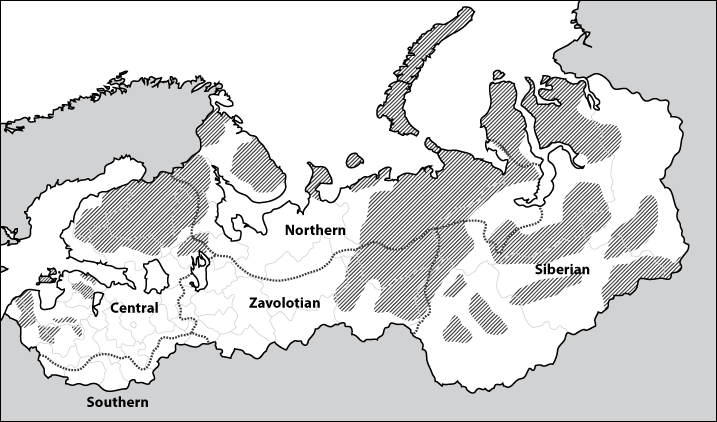

Novegradian has five major dialect zones, as shown in the map below. These groups are typically identified as “Central” (including standard Novegradian), “Southern”, “Zavolotian”, “Northern”, and “Siberian”. Each of these can then in turn be divided into a number of subdialects.

It should be noted that the following discussion is purely about spoken dialects (as very little written variation exists). When comparing them to standard Novegradian, therefore, it is best to compare them to the spoken form of the language as described in the previous section rather than the written standard. Unless otherwise noted, most of the changes described in Section 22 are also present in the various dialects, such as nominative ending loss, possessive endings, and the vocative case.

The map above shows the geographic distribution of the five major dialect groups, represented by the large dashed lines. This, however, is largely based on traditional usage, and does not indicate the widespread use of central dialects closer to Standard Novegradian in major cities throughout the country.

Shaded regions represent areas where the first language of most of the population is not Novegradian, so that the majority of speakers learn Novegradian at a later age.

23.2 The Central Dialects

The Central Dialects are the Novegradian dialects spoken in the oldest part of the country, centered around the cities of Novegráde Velíkei, Pleskóve, and Néugrade. It is also spoken in the Baltics and much of Finland and southern Karelia, where it was introduced after these territories were annexed between the late 17th and mid 18th centuries. The standard language is based on the Velikonovegrádeskei subdialect.

23.2.1 Geographic Distribution

The standard dialects are centered in the Novegradian heartland around Novegráde Velíkei itself. As the standard variety, this dialect was also spread into the Republic’s newest territories, those annexed after the language was largely standardized. There are also smaller groups of central dialect speakers scattered throughout the nation, particularly in recently-founded far-northern cities such as Murmáne and Suětlogóreske, which were settled in the 20th century and whose populations were largely transplanted to these locations during the Soviet period. Many people in major cities throughout the country speak a central dialect due to increasing mobility in recent years, although in many smaller cities and the countryside the local dialects may still be dominant.

23.2.2 History

The city of Novegráde Velíkei has always been the capital and cultural center of the Novegradian state, and as such its dialect has always been the most prestigious form of Novegradian.

23.2.3 Status

The standard dialects are viewed as the most neutral form of the language. It is the most commonly heard speech variety on television and radio, and is generally preferred in business and political contexts. The written form of Novegradian is based on these dialects as well.

However, locally there is some variation in what is viewed as standard speech. Although the written standard is common across the entire nation, the Lětnosúmeskei (Southern Finland) subdialect, which features some differences in pronunciation from the standard Velikonovegrádeskei subdialect, is viewed as the more or less official spoken dialect within the Republic of Finland. Most people, including Finnish politicians and newscasters, will follow this pronunciation standard even in more formal contexts. Primary schools will often teach the official Novegradian pronunciation, but put little emphasis on it and then continue on in using Lĕtnosúmeskei pronunciation. Similar situations may be seen in Latvia and, to a lesser extent, Estonia and Komi.

23.2.4 Phonology

The pronunciation of standard Novegradian as well as more its colloquial counterpart has been discussed earlier in this grammar. However, the subdialects spoken in Finland and Latvia deserve mention since they will be heard throughout these regions.

Some Finnish features include:

- Unstressed /æ/ generally is not merged with /i/.

- /sʲ/ becomes /s/ when part of a cluster: поста pósta “mail” (standard пошта póśta); similarly, /zʲ/ becomes /z/.

- /ɫ/ is pronounced as /l/, often with a /u/~/w/ inserted before or after: соулдат souldát “solder” (standard сољдате sołdáte), луовити luóviti “catch” (standard љовити łóviti).

- The palatals /c ɟ ç ʝ/ are pronounced [kʲ gʲ xʲ ɣʲ], except in coda position, where they merge with the velar series as [k g x ɣ], albeit with a [ɪ̯] on-glide. Standard нокьи nókji “night”, for example, will be pronounced [ˈno.kʲɪ] in formal contexts or [ˈnoɪ̯k] informally.

- A glottal stop is inserted between a prefix and a root beginning with a vowel, instead of /j/ in the standard: оавити o’áviti “declare” (standard оявити oiáviti).

- More sporadically, the stressed front vowels /æ e i/ sometimes diphthongize to /æi ei ie/ in open syllables.

- Final /in/ lowers to /en/.

- Final /e/ in the lative or accusative clitic pronouns becomes /jæ/: миѣ, тиѣ, etc.

Some Latvian features include:

- Final vowels in definite ending endings tend to drop: цервенай cervénai “red (nom.sg.fem)” (standard цервеная cervénaia).

- Unstressed vowels in nominal endings followed by a consonant tend to drop or weaken greatly: морм mórm “sea (datins.sg)” (standard морем mórem).

- /ɨ/ pronounced as /ə/: гымати [ˈgə.mə.tɪ] (standard [ˈgɨ.mə.tɪ]) “shout”.

- /n/ before a stressed front vowel is realized as a fully palatal [ɲ] instead of palatalized [nʲ]: ньет njét “no” (standard нет nét).

- /b/ in oblique forms of 2sg and reflexive pronouns pronounced /β/: шеве śevé “oneself (acc)” (standard шебе śebé)

23.2.5 Grammar

Once again, the grammar of standard Novegradian has been previously discussed.

The most defining feature of the grammar of the semi-standard Finnish dialect is its use of the partitive case. It uses the partitive after numerals instead of the genitive or count forms: довѣ нигох dóvě nígoh “two books” (standard довѣ нигѣ dóvě nígě). It also uses the partitive case instead of the accusative to mark the direct object of positive stative verbs: Яс лублун Маркех Iás lublún Markéh “I love Mark” (standard Яс лублун Марка Iás lublún Márka). It is not uncommon to hear the partitive singular ending -ох -oh (already reduced from standard -ок -ok) simplify to just -о -o in casual speech.

The grammar of the Latvian dialects does not vary significantly from standard Novegradian. The most noticeable difference is the tendency to place adverbs clause-finally, instead of in front of the verb, which often sounds quite strange to other Novegradian speakers. The reduction of a number of nominative and genitive case definite adjective endings is also a distinctive feature, and is different from the reductions seen in colloquial speech of other dialects:

|

Latvian

Formal/Spoken |

Standard

Formal |

Standard

Spoken |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nom Sg M | цервеней cérvenei |

цервеней cérvenei |

цервеней cérvenei |

| Nom Sg N | цервеной cervénoi |

цервеное cervénoie |

(цервение cervénie) |

| Nom Sg F | цервенай cervénai |

цервеная cervénaia |

цервеня cervénia |

| Nom Pl | цервений cervénij |

цервение cervénije |

цервенеи cervénji |

| Gen Sg M/N | цервенайв cervenáiv |

цервенаево cervenáievo |

цервенайво cervenáivo |

| Gen Sg F | цервенѣй cervéněi |

цервенѣе cervéněie |

цервенѣе cervéněie |

23.3 The Southern Dialects

23.3.1 Geographic Distribution

The Southern dialects cover the smallest area geographically out of all the major Novegradian dialect groups, but include several large population centers. They form a narrow belt hugging the southwestern Novegradian border along Russia and Belarus. It is spoken in the southern halves of Lovotiskáia, Reźeveskáia, and Moloźeskáia oblosts, the western half of Mostegradeskáia oblost, and most of Videbeskáia and Poloteskáia oblosts.

23.3.2 History

These dialects have had a large amount of influence from East Slavic languages, particularly Russian and Belarussian. Lying on the edge of Novegradian-speaking territory, these people have historically lived with and had frequent contact with Russians and Belarussians. In fact, many speakers of southern dialects, particularly in the westernmost parts of the region, are of Russian descent, most of whom have since been assimilated. When Russia and Novegrad were unified from the 19th century until 1917, this more Russified dialect spread further northward as it gained more prestige, but after 1917 and the reassertion of Novegradian nationalism began once again to retreat to the border region.

23.3.3 Status

Once a somewhat prestigious dialect, it is now somewhat stigmatized. Due to rising Novegradian nationalism in the early 20th century and particularly since the 1970s, there has been a greater desire to remove many perceived Russianisms from the language.

The southern dialects have no official support, and exist principally on a colloquial level. In formal situations speakers are expected to use Standard Novegradian (or if they live within the borders of the Latvian Republic, the standardized Latvian dialect of Novegradian).

23.3.4 Phonology

The following describes the Vidébeskei subdialect.

23.3.4.1 The Vowel System

Three features stand out in the vocalic system. The first is the presence of akanye (аканье ákanje), common in East Slavic languages but nonexistant in most varieties of Novegradian. In these dialects, unstressed /o/ merges completely with /a/: гавариты gavaríty “talk” (standard говорити govoríti). This can sometimes lead to gender confusion, as an unstressed final /o/ will merge with unstressed final /a/: яблака iáblaka “apple” (standard яблоко iábloko). Note that this means colloquially many neuter third declension nouns are merging with the feminine in the South, whereas in other dialects all neuter nouns are merging with the masculine.

Second is the loss of the yat /æ/. When stressed it becomes /ja/, and when unstressed /e/: вяра viára “faith” (standard вѣра vě́ra), наляве naliáve “on the left” (standard налѣвѣ nalě́vě).

Third is the phoneme /ɨ/, which appears natively. It is pronounced slightly further forward than standard Novegradian /ɨ/. It has three main sources: from foreign loans, as in the standard: гыматы gymáty “shout” (standard гымати gymáti); from Common Slavic *y, which is usually /i/ or /wi/ in the standard: быты býty “be” (standard буити buíti); and from unstressed /i/ when word-finally or before a nasal consonant (i.e., where the standard has [ɪ]): пяты piáty “sing” (standard пѣти pě́ti).

Additionally, many places where /e/ [je] appears at the beginning of a word in standard Novegradian that derives directly from Common Slavic, southern dialects will instead have /o/ (which can be realized as /a/, as per above, or /βo/, as per another rule described below): водене vódene “one” (standard едене iéden), вожера vóźera “lake” (standard ежеро iéźero). The presence of /o/ for standard initial /e/ is highly inconsistent across subdialects, suggesting dialect borrowing may be a contributing factor.

23.3.4.2 Vowel Alterations

/o/ is not allowed to appear word-initially in native words, as /β/ must be added before. This often leads to a stressed /βo/ versus unstressed /a/ alteration: nom.sg акно aknó “window”, gen.sg вокну vóknu (standard окно oknó, окну óknu). Standard Novegradian has a similar feature, where [w] is added before an initial stressed /o/, though this does not appear in writing.

Many nouns with an unstressed /e/ in the singular that undergo a stress shift to that vowel in the plural will see an /e/ → /o/ shift when stressed. This is another feature very common in East Slavic languages: вожера vóźera “sea”, ажоры aźóry “seas” (standard ежеро iéźero, ежера ieźerá).

23.3.4.3 Consonants

The consonant system of southern dialects is actually quite similar to the standard.

The most noticeable difference is the sporadic application of the Second Slavic Palatalization, which most forms of Novegradian skipped. This results in */k g x kv gv xv/ becoming /ts z s tsw zw sw/ before front vowels in these dialects: зўязда zwiazdá “star” (standard гуѣзда guě́zda). Веше véśe “all” (standard вехе véhe), an instance of the progressive palatalization not seen in standard Novegradian, is also commonly heard.

Another feature is cókanje (цоканье cókanje), the confusion of /tʃ/ and /ts/. Standard Novegradian went through this stage, but ultimately converted all original instances of both /ts/ and /tʃ/ to /ts/. In southern dialects, the two forms now exist in allophonic variation, with [tʃ] before front vowels and /j/ and [ts] elsewhere: чидаты čidáty “read” (standard цидати cidáti), цай cái “tea” (standard цае cáie).

Standard Novegradian /ɫ/ has merged with /w/, and /ɲ/ is generally pronounced as a geminate /nn/: жоуте źóute “yellow” (standard жољте źółte), веденне vedénne “knowledge” (standard вѣденье vědénje).

23.3.5 Grammar

Southern dialects have all the same nominal and adjectival declensional forms as the standard, although their pronunciation is often different. The total number of declensions has dropped, however, due to the loss of the third declension O-stems.

The two biggest changes that cannot simply be explained by sound changes are the loss of the nominative plural ending -a for neuter nouns (now -y for all nouns), and the singular forms of sixth-declension nouns. Such nouns display their suffixed forms only in the plural. In the singular, мат mát “mother” and докь dókj “daughter” behave as fifth declension nouns, while all others take the suffix -ие -ie and conjugate as fourth declension nouns. Additionally, the dative/instrumental ending for sixth declension nouns is often -u instead of -em, derived from the historical dative form instead of the instrumental as in the standard.

| Singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| нига “book” | жемла “land” | вожера “lake” | мор “sea” | нокь “night” | имие “name” | |

| Nom | нига níga |

жемла źémla |

вожера vóźera |

мор mór |

нокь nókj |

имие ímie |

| Gen | ниге níge |

жемле źémle |

вожере vóźere |

мора móra |

нагьи nagjí |

имя ímia |

| Acc | нигу nígu |

жемлу źémlu |

вожеру vóźeru |

мор mór |

нокь nókj |

имие ímie |

| D/I | нигой nígoi |

жемлей źemléi |

вожерой vóźeroi |

морем mórem |

нагьюм nagjiúm |

имю ímiu |

| Part | нигох nígoh |

жемлох źemlóh |

вожерох vóźeroh |

морех moréh |

нокьех nókjeh |

имиех ímieh |

| Loc | ниге níge |

жемле źemlé |

вожере vóźere |

море móre |

нагьи nagjí |

имие ímie |

| Lat | нигун nígun |

жемлун źemlún |

вожерун vóźerun |

морен morén |

нокьын nókjyn |

имиен ímien |

| Voc | нигма nígma |

жемлама źémlama |

вожерма vóźerma |

морма mórma |

нокьма nókjma |

имиема ímiema |

| Plural | ||||||

| Nom | нигы nígy |

жемле źémle |

ажоры aźóry |

моры móry |

нокьие nókjie |

ымоны ymóny |

| Gen | ниг níg |

жемел źemél |

ажор aźór |

мор mór |

нокьей nókjei |

ымон ymón |

| Acc | нигы nígy |

жемле źémle |

ажоры aźóry |

моры móry |

нокьие nókjie |

ымоны ymóny |

| D/I | нигам nígam |

жемлам źemlám |

ажорам aźóram |

морам morám |

нагьям nagjiám |

ымонам ymónam |

| Part | нигуо níguo |

жемлоу źemlóu |

ажеруо aźeruó |

мореу móreu |

нокьеу nókjeu |

ыменуо ymenuó |

| Loc | нигах nígah |

жемлах źemláh |

ажорах aźórah |

морях moriáh |

нокьих nókjih |

ымонех ymóneh |

| Lat | нигы nígy |

жемле źémle |

ажоры aźóry |

море móre |

нокьы nókjy |

ымоны ymóny |

| Voc | нигыма nígyma |

жемлема źémlema |

ажорыма aźóryma |

морыма móryma |

нокьиема nókjiema |

ымоныма ymónyma |

Indefinite adjectives decline much like nouns. However, some of the definite forms are more reduced than in the standard. The neuter forms are shown in the following adjective table, but are increasingly rare in speech. Shown are червенай čérvenai “red” (an antepenultimate-stress adjective in the standard) and другой drugói “second” (an ending-stress adjective in the standard, which here has ending stress even in its nom.sg.masc form).

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | червенай čérvenai |

червенае červénaie |

червеная červénaia |

червеные červényie |

другой drugói |

другое drugóie |

другая drugáia |

другие drugíje |

|

| Genitive | червенага červénaga |

червеняй červéniai |

червеных červényh |

другога drugóga |

другяй drugiái |

других drugíh |

|||

| Accusative | червенай čérvenai |

червенае červénaie |

червенаю červénaiu |

червеные červényie |

другой drugói |

другое drugóie |

другаю drugáiu |

другие drugíje |

|

| Dat/Instr | червенаму červénamu |

червенаюн červénaiun |

червенымы červénymy |

другому drugómu |

другоюн drugóiun |

другымы drugýmy |

|||

| Partitive | червенага červénaga |

червеновага červenóvaga |

другога drugóga |

друговага drugóvaga |

|||||

| Locative | червеняйм červéniaim |

червеняйх červéniaih |

другяйм drugiáim |

другяйх drugiáih |

|||||

| Lative | червенуюн červénuiun |

червенее červéneie |

другуюн drugúiun |

другее drugéie |

|||||

Most southern dialects preserve the original /g/ in the genitive ending, which became /β/ in standard Russian and Novegradian. This is seen in pronouns as well, such as the third person masculine accusative pronoun его iegó (occasionally вого vogó), versus standard ево ievó.

These definite adjectives may function as nouns by themselves, as in standard Novegradian, but in order to do so the demonstrative то tó “that” must be declined to the appropriate gender, case, and number and cliticize to the end of the adjective. In southern dialects, то still has a full declension paradigm: червеные-ты červényie-ty “the red ones (nom.pl)”, другога-таго drugóga-tagó “of the other one (gen.sg.m/gen.sg.n)”.

The personal pronouns and possessive adjectives are largely the same as in the standard, although they include the features mentioned above. However, possessive adjectives are used more frequently in southern dialects than in the standard, where they are being replaced by the preposition о “at”. The second person singular and the reflexive possessive adjectives have a unique form in the nominative singular masculine: тавой tavói and савой savói (standard туой tuói and суой suói), which both have gained an epenthetic vowel.

23.4 The Zavolotian Dialects

23.4.1 Geographic Distribution

The Zavolotian dialects are dominant throughout much of the eastern portion of European Novegrad (Zavolotia), on the west side of the Ural Mountains, and in some communities on the eastern slopes of the Urals. It is spoken throughout most of the non-Arctic-littoral oblosts, although it is seen in the southern half of Brězéuskaia and Pečarouskáia oblosts.

23.4.2 History

These regions are historically the first areas penetrated by Novegradian traders, explorers, and settlers beyond the core of the original Novegradian state. It has had somewhat less Russian influence than the standard, but a great deal more from indigenous languages, particularly Komi. And while the more western parts of the country have historically looked westward, the settlers of this territory turned eastward for growth, focusing on trade with the East and expansion into the vast, sparsely-populated yet rich territories toward and beyond the Urals. Due to the region’s important historical trading centers, the Zavolotian dialects have borrowed vocabulary from a number of Turkic and Central Asian languages as well, some of which then entered the speech of western Novegradians.

23.4.3 Status

While it has no official support (except perhaps in the Komi Republic), the Zavolotian dialects are nevertheless considered a respectable manner of speech, although a particularly thick accent may be seen as somewhat rustic in major cities of western Novegrad. People are expected to use standard Novegradian in formal situations.

23.4.4 Phonology

The following is based on the Volóğdeskei subdialect.

23.4.4.1 Vowels

The Zavolotian dialects have undergone a number of vowel changes and small shifts, one of the most distinctive features of this group of dialects. There appears to be general trend toward closing vowels. Vowel changes can be divided into the following categories:

Denasalization: Zavolotian dialects handled the Proto-Slavic nasal vowels slightly differently than the standard. Proto-Slavic *ǫ become /u/ word-finally: говору govorú “I talk” (standard говорун govorún); and /o/ elsewhere: крог króg “circle” (standard краге kráge, but note рока róka “hand”). Proto-Slavic *ę, on the other hand, becomes /e/ in all positions: агне agné “lamb” (standard агнин agnín), пете péte “five” (standard пети péti).

Yat’ Loss: When stressed, yat’ /æ/ became /je/: виек viék “century” (standard вѣке vě́ke). When unstressed, it becomes just /e/: видете vídete “see” (standard видѣти víděti).

Diphthongal Shifts: The diphthongs /au/ and /eu/ (including those involving a former /β/) both simplify into /o/ in all positions: отобус otóbus “bus” (standard аутобусе áutobuse), Ёропа Iorópa “Europe” (standard Еуропа Ieurópa). /oj/ is raised to /uj/ in all positions: вуйна vuiná “war” (standard война voiná). Both /aj/ and /ij/ merge into /ej/: чей čéi “tea” (standard цае cáie), Рошзея Rośzéia “Russia” (standard Рошзия Rośzíja).

Initial Epenthesis: Word-initial /o/ and /u/ both acquired an epenthetic /β/ early on: воко vóko “eye” (standard око óko), вудчите vudčíte “teach” (standard оѕити odzíti). This change does not affect later loan words or words that latter gained an initial /o/ or /u/ by other changes, but rather only words with these vowels inherited directly from Common Slavic. Note, however, that Zavolotian dialects lost the [j] before word-initial /e/ seen in the standard. And like the Southern dialects, a number of words beginning with /e/ in the standard begin with /βo/ in these dialects: вожеро vóźero “lake” (standard ежеро iéźero).

/w/-Induced Shifts: C+/w/ clusters (again, many of which once were C+/β/) caused shifts in the following vowel, drawing them back. C+/wæ/ sequences all became C+/wa/: суат suát “light” (standard суѣте suě́te). C+/we/ sequences all became C+/wo/, though the /w/ later dropped: доре dóre “door” (standard дуери duéri). The loss of /w/ before /o/ affected original */o/ as well: туй túi “your” (earlier form той tói; standard туой tuói).

Stressed Closed Syllable Shifts: In closed syllables, stressed /a/ is raised to /e/ and /o/ is raised to /u/: гред gréd “city” (standard граде gráde “city”), вуз vúz “car” (standard возе vóze).

Other Closed Syllable Shifts: The vowel /o/ before /n/ in a closed syllable always becomes /i/, overriding the rule above: вин vín “he” (standard оне óne).

Final Vowel Changes: Final /e/ has been universally lost in the nominative singular masculine (though not neuter) endings, creating many of the closed syllables seen above. A later change, however, then shifted all final /i/ to /e/: поте póte “way” (standard панти pánti). Final /ja/ (when after a consonant) metathesizes to /aj/, probably via */jaj/: жемай źemái “land” (standard жемя źémia).

VjV Simplification: There is a tendency to drop intervocal /j/ when the first V is unstressed, resulting in the second vowel dominating: добре dobré “good (nom.sg.neut.def)” (standard доброе dóbroie). /eja/ appears to be resistant in endings, however: Англея Ángleia “England” (standard Англия Ánglija). If the vowels on both sides of the /j/ were the same, they will collapse into one, no matter the stress: раѕет radzét “(he) enjoys” (standard радеет radéiet). If the first vowel is stressed, the second vowel tends to drop: другой drugói “second (nom.sg.neut.def)” (standard другое drugóie).

/xo/-Shift: The sequence /xo/ shifted to /xe/ in all circumstances: хедите hédite “go” (standard ходити hóditi).

23.4.4.2 Consonants

The Zavolotian dialects developed their early consonant system in much the same way as the standard did. Most consonant divergences are relatively recent, having occurred only within the last 200 years or so. Again, these can be grouped into a number of categories:

Palatalization: Before stressed front vowels or /j/, the consonants /t d l/ undergo a full palatalization, merging with other phonemes. /t/ and /d/ both become hard (non-palatalized) affricates: че čé “you” (standard ти tí), ѕевете dzévete “nine” (standard девити déviti). /l/ in the same environment virtually disappears, becoming /j/: иете iéte “pour” (standard лѣти lě́ti). Note that these changes happened before the /a/ → /e/ shift above, so words such as дем dém “I give” (standard дам dám) remain unaffected.

Depalatalization: In the standard dialects, the consonants /s z n k g x/ become palatalized before a stressed front vowel. In central dialects no such palatalization occurs: нига níga [ˈni.gə] “book” (standard [ˈnʲi.gə]). The actual phonemes /sʲ zʲ/, however, still remain and no longer overlap with /s z/ + front vowel.

Further Depalatalization: /s/ and /sʲ/ sporadically convert to /x/ before another consonant. Some of these can be attributed to analogy (such as страхне stráhne “frightening” from страхе “fright”; standard страшне stráśne), but others are much less obvious: вуихла vuíhla “(she) exited” (standard вуишла vuiślá).

Assimilation: The clusters /dn/ and /tn/ both become /nn/: кланно klánno “cold” (standard кладно kládno).

Chokanye: Zavolotian dialects, like southern dialects, completely merged /tʃ/ and /ts/, yet have both [tʃ] and [ts] appear as surface realizations of this new merged phoneme—as [tʃ] immediately before a stressed vowel and as [ts] in all other positions. Many words will show an alternation as stress shifts: червен čérven “red (nom.sg.masc)” (standard цервене cérvene), цервен cervén “red (gen.pl)” (standard цервен cervén).

Loss of /ɲ/: The phoneme /ɲ/ uncouples, becoming /jn/. This occurred before the diphthongal changes mentioned earlier occurred, so this frequently causes vowel mutations: виѕан vidzán “vision, sight” (via earlier виѕѣйне; standard видѣнье vidě́nje), ейней éinei “angel” (via earlier айнее; standard аньее ánjeie).

Loss of /ɫ/: The phoneme /ɫ/ disappears word-initially and pre-consonantally: содат sodát “soldier” (standard сољдате sołdáte). If the /ɫ/ is word-initial before /o/ or /u/, the standard epenthetic /β/ will take its place: вовите vóvite “catch” (standard љовити łóviti).

Loss of /ɣ/: The phoneme /ɣ/ becomes a glottal stop [ʔ] in all positions. However, this change occurred after /ɣ/ palatalized to /j/ before front vowels: бо’ bó’ “God” (standard боғе bóğe).

Complete /dl/ → /gl/: The Zavolotian dialects converted old Novegradian /dl/ to /gl/ in all positions, even word initially, whereas the standard preserved it word initially. As a result, the Zavolotian dialects have forms such as глане gláne “palm” and глитиш glítiś “span” (standard длани dláni and длитиш dlítiś).

23.4.5 Grammar

In the Volóğdeskei subdialect, the dual ending -а -a seen in the present/future tense was changed to -ай -ai (by analogy with the /aj/ diphthong seen in a number of other dual words in the dialect, including the dual possessive adjectives, the numeral “two”, and the pronoun “both”), though this later changed to /ej/ by regular changes. The closed syllable vowel changes also clearly took place before the loss of final /t/ in the third person plural endings.

Note the generalization of the 2sg ending -ш -ś to the athematic verbs, replacing standard stressed -жи -źí. The third (E) conjugation has also merged the 1sg and 3pl forms.

|

цидате

“read” |

говорите

“talk” |

жите

“live” |

дате

“give” |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Sg | цидем cidém |

говору govorú |

живу źivú |

дем dém |

| 2Sg | цидеш cidéś |

говориш govoríś |

живеш źivéś |

деш déś |

| 3Sg | цидес cidés |

говорит govorít |

живет źivét |

дес dés |

| 1Dl | цидавей cidávei |

говоривей govorívei |

живевей źivévei |

давей dávei |

| 2Dl | цидастей cidástei |

говоритей govorítei |

живетей źivétei |

дастей dástei |

| 3Dl | цидастей cidástei |

говоритей govorítei |

живетей źivétei |

дастей dástei |

| 1Pl | цидаме cidáme |

говорим govorím |

живем źivém |

даме dáme |

| 2Pl | цидате cidáte |

говорите govoríte |

живете źivéte |

дасте dáste |

| 3Pl | циде cidé |

говоре govoré |

живу źivú |

дада dáda |

The Volóğdeskei dialect has distinct passive and middle voice clitics, -шен -śen and -ше -śe respectively. The passive form is borrowed from the standard, as it never developed locally. In some of the easternmost Zavolotian dialects, however, neither -шен nor any other equivalent passive form came into being. -ше is used exclusively for the middle voice, while the passive voice is expressed using participles.

Negation is generally expressed with на na (phonetically [nə]; standard не ne). However, when stressed, this negative particle reverts back to не né.

The nominal system has been relatively stable, and most changes to it can be explained by regular sound changes. Very distinctive is the use of -е -e to indicate the nominative plural for all nouns, instead of the usual -и -i. Second declension nouns like жемай źemái “land” have a strange form in the nominative singular, but in all other cases the stem is *źemj-, lacking /l/ in all forms: жемю źémiu “land (acc.sg)” (standard жемлу źémlu). The neuter gender remains strong, unlike all other Novegradian dialect groups.

Due to the VjV simplification sound changes, the definite adjective declension is very different compared to the standard, particularly for antepentultimate-stress adjectives like червен čérven “red”. Ending-stress adjectives such as друг drúg “second” only differ in the nominative case: другей drugéi (m), другуй drugúi (n), другей drugéi (f), другие drugíje (pl).

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom | червеней čérvenei |

цервене cervené |

цервена cervená |

цервене cervené |

| Gen | цервенейво cervenéivo |

цервене cervené |

цервених cerveníh |

|

| Acc | червеней čérvenei |

цервене cervené |

цервену cervenú |

цервене cervené |

| Dat/Instr | цервенем cerveném |

цервенуй cervenúi |

цервениме cerveníme |

|

| Part | цервенейво cervenéivo |

цервеновуо cervenóvuo |

||

| Loc | цервением cerveniém |

цервених cerveníh |

||

| Lat | цервенун cervenún |

цервение cervenié |

||

The definite adjective suffixes have all undergone a significant amount of merger and analogy. Ending stress is universal throughout (except in the nom/acc sg); the two historical stress patterns still seen in the standard have evolved into two adjectival declensions instead, with some nouns (for example) taking the nom.sg.neut ending -е -e and others -уй -ui.

Personal pronouns function in much the same way as spoken standard dialects (including the use of clitics). However, their forms are significantly different. Below are their nominative case forms.

| Sg | Dl | Pl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | я iá | надуа nádua | ме mé |

| 2nd | че čé | вадуа vádua | ве vé |

| 3rd |

вин vín

на ná |

вида vidá | не né |

The changes to several of the prepositions made them homophonous with other common words. To eliminate this confusion, the preposition на ná “on” became ней néi (derived from a variant Proto-Slavic form *naj, seen for instance in the superlative prefix). The reduction of the negative particle was discussed above, though it can also be reinforced using the phrase ни виегье ni viegjé “not a thing”: Я на соѕиелал шево ни виегье Iá na sodziélal śevó ni viegjé “I didn’t do this.” In connected speech this can reduce to нивгье nivgjé or нигье nigjé.

Sounds changes also created vowel alterations in the possessive adjectives. Shown below are the nominative case forms.

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Sg | муй múi | мие mié | мя miá | мие mié |

| 2Sg | туй túi | тие tié | тя tiá | тие tié |

| 1Dl | нейн néin | ней néi | ня niá | ние nié |

| 2Dl | вейн véin | вей véi | вя viá | вие vié |

| 1Pl | неш néś | наше náśe | наша náśa | наше náśe |

| 2Pl | веш véś | ваше váśe | ваша váśa | ваше váśe |

| Reflex. | суй súi | сие sié | ся siá | сие sié |

The third person forms are ево ievó “his”, ие ié “her”, ё ió “them two’s”, and ех iéh “their” in all forms.

As in the standard, however, a prepositional form is becoming more common in speech:

| Sg | Dl | Pl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | вумне vúmne | воней vonéi | вонес vonés |

| 2nd | воче vočé | вовей vovéi | вовес vovés |

| 3rd |

вунуо vúnuo

вуние vúnie |

вуню vuniú | вуне vúne |

| Reflex. | воше vośé | ||

The standard method of indicating approximations of numbers by inverting the numeral and the quantified noun (e.g., дешити минут déśiti minút “ten minutes” vs. минут дешити minút déśiti “about ten minutes”) is not used in most Zavolotian dialects. Both orderings may be used, but the only difference is which element is emphasized. Instead, approximations are formed by prefixing не- ne- onto the numeral: неѕешете минут nedzéśete minút “about ten minutes”. This is also seen in the Northern and Siberian dialects.

23.5 The Northern Dialects

23.5.1 Geographic Distribution

The Northern dialects are the dominant spoken form of Novegradian along the Arctic littoral, from the Kola Peninsula to the Ob Gulf.

23.5.2 History

The Northern dialects originate with the dialect of the Pomors (or kodzári), the first Novegradian settlers along the coast of the White Sea. As they explored the Arctic coastline, they spread their dialect along with them. With the founding of major port cities such as Arhánjeiske, the northern dialects became the standard among Novegradian shipping and trading circles. The kodzári being the first colonial settlers of the Ob valley and from there into Siberia, a dialect continuum exists in northern Siberia, with more typical Northern dialectical features towards the north and Siberian dialectical features towards the south.

Due to its use as an historical trading language, it has borrowed vocabulary from many different languages, not only local languages such as Komi, Nenets, and Saami, but also regional shipping languages such as Norwegian, Dutch, and English.

23.5.3 Status

Though the dialect has no official support, its usage remains strong. Its use is a matter of pride to many northerners, so it will often be seen on shop signs and other locations in cities. However, people are expected to use the standard grammar and pronunciation in formal situations.

23.5.4 Phonology

The following is based on the Arhánjeiskei dialect.

Northern dialects have not diverged significantly from the standard form, phonologically speaking. Changes can be grouped into the following categories.

Loss of Nominative /e/: As in most dialects, the final /e/ seen in the nominative/accusative singular of masculine nouns and adjectives is lost, though the consonant before does not lose its voicing. As in the central dialects, the fourth declension nominative ending -i then shifted to -e.

Cluster Simplification in the Nominative: Most final clusters were simplified, usually by deleting an element or by inserting an epenthetic vowel, generally /i/ or /e/: мус mús “bridge” (standard мосте móste), верех véreh “top” (standard врех vréh, from Common Slavic *vьrxъ). Note that these clusters often return when the noun is declined and an ending is added, as is seen in their plural forms: моста mostá, верха verhá. Other changes are harder to predict, such as the form дожже dóžže “rain” (pronounced [doʒ.ʒe]; standard дожгьи doźgjí), which has the stem *дожгь- *doźgj- in all other cases.

Other Cluster Simplification: Other cluster simplifications occur in all forms of a word, such as the simplification of /tn dn/ → /nn/ and /pm bm/ → /mm/.

Lenition of /v/: The northern dialects have shifted the pronunciation of standard /β/ to the labiodental [v]. It also behaves as a normal fricative, meaning it is not weakened to /w/ preconsonantally or word-finally. Word-finally or before unvoiced consonants it becomes /f/, indicated orthographically with the Russian letter ф.

Realization of *y: Proto-Slavic *y becomes /u/ in all positions except finally. In the standard it varies between /i/ and /wi/: пудати pudáti “ask” (standard пуидати puidáti).

Realization of Yat’: The yat’ /æ/ becomes /i/ in all positions: ида idá “food” (standard ѣда iědá).

Realization of *jь: Where Proto-Slavic *jь became /j/ or /ji/ in the standard, it becomes /i/ in the northern dialects: име íme “name” (standard ймѣно jmě́no; compare archaic variant ймѣ jmě́).

Yer-Raising: The front yer *ь may sporadically be raised to /i/ when stressed: дин dín “day” (standard дене déne), вих víh “all” (standard вехе véhe).

Lenition of /g/: The phoneme /g/ (including what is /ɣ/ in the standard) lenites to /x/ word-finally: бох bóh “God” (standard боғе bóğe).

Loss of Intervocalic /j/: Intervocalic /j/ is lost in the nominative definite adjective endings and in verb endings.

Vowel Changes: There are several other miscellaneous vowel shifts seen in northern dialects. First is the unconditional change /ja/ → /je/: еблоко iébloko “apple” (standard яблоко iábloko). Second is the change /o/ → /u/ in stressed closed syllables, as seen in мус “bridge” above. Last is the change /e/ → /a/ after the consonants /sʲ zʲ ts dz tʃ/ (and after /s z/ only if the /e/ is unstressed): шастра śastrá “sister” (standard шестра śéstra). In addition, the sequence /xo/ consistently fronted to /xe/: хедите hédite “go” (standard ходити hóditi).

Handling of Yer Dropping: The Proto-Slavic ultrashort vowels /ъ/ and /ь/ were generally lost when unstressed and kept when stressed. However, in standard Novegradian, they were also kept whenever dropping them would create an awkward cluster. The northern dialects went ahead and dropped all unstressed yers in the initial syllable of a word, inserting an epenthetic /i/ at the beginning of the word. This means many words gain a prefix as well as a suffix when they are conjugated or declined: рот rót “mouth”, plural ирта irtá (standard роте róte, роти róti, though compare Russian plural рты rty). The same occurs even when the cluster would be no trouble to pronounce, as long as it was created by yer dropping: сон són “dream”, plural исна isná (standard соне sóne, сони sóni). If too awkward of a cluster would occur anyway if the yer were dropped, conflicting forms appear. Some dialects regularize the noun, as in верех véreh “top” → верха verhá as shown above (instead of **иврха ivrha). Others regularize the noun but still add the prefix, giving the plural иверха iverhá.

23.5.5 Grammar

The Northern dialects are perhaps more notable for their grammatical divergences from standard Novegradian than for their phonological ones.

23.5.5.1 Verbs

Verbs are much the same as the standard, with the following significant divergences:

Double Vowel Simplification: Due to /j/-dropping, any sequence of a vowel twice in a row is reduced to one: радет radét “(he) enjoys” (standard радеет radéiet).

Stress in the Dual and Second Person Plural: In verbs that are ending stressed, the stress in the present/future tense is always placed on the last syllable, not on the first syllable of the ending. This gives forms such as цидава cidavá “the two of us read” (standard cidáva), цидаста cidastá “you two/them two read” (standard cidásta), and цидате cidaté “you all read” (standard cidáte). The 3pl form of the first conjugation does not do this, as the final /ti/ has been dropped: цида cidá “they read” (standard цидати cidáti).

3pl Forms: The 3pl suffix in the present/future forms of all conjungations has been lost: цида cidá “they read”, луба lúba “they love”, пихьа píhja “they write”. The 3pl ending for athematic verbs is -а: еса iésa “they are”, дада dáda “they give”, etc. Note how the ending -а has been generalized to all conjugations.

Synharmony: The process of syllabic synharmony, which affected all of the Slavic languages from the Proto-Slavic period up through the Middle Ages (see the Historical Phonology), has continued in the Northern dialects where it had stopped in the standard. This is particularly visible in the 1sg present tense form of many verbs. Like in medieval Czech, the vowel /i/ appears instead of /u/ whenever the preceding consonant has undergone morphological palatalization (i.e., is different from the consonant in the infinitive): я пихьин iá píhjin “I am writing” (standard яс пихьун iás píhjun), but я будун iá búdun “I will be” (standard яс бадун iás bádun). This is also always seen for all second conjugation verbs: я говорин iá govorín (standard яс говорун iás govorún), since this ending comes from an older *-jǫ.

Future Tense: The future tense of imperfective verbs is not marked using be+infinitive, but rather with the present-future form and the non-declining particle хекь hékj or хе hé (derived from the verb хотѣти hótěti “want”), which can appear either immediately before or after the verb. The form буте búte “be” + infinitive is generally used as a variant of the future hypothetical form буте + past. The future tense of “be” may be marked either by the future tense forms of буте alone (e.g., будун búdun “I will be”), or the future tense forms combined with one of these particles (e.g., хе будун hé búdun).

Infinitives of Roots Ending in Velar Consonants: Standard Novegradian forms marks the infinitive of verb roots ending in /k g/ with -йкьи -ikji. Northern dialects generally reinsert the dropped consonant and use the regular -t- ending: могте mógte “to be able to” (standard мойкьи móikji), плакте plákte “cry” (standard плайкьи pláikji).

One unique verb form seen in some Northern dialects is the phrasal past perfective, which exists in free variation with the analytic perfective past form, though only when the subject is a pronoun. The subject is expressed as a declined form of the preposition о o “at” followed by a non-declining verb form identical to the neuter indefinite perfective passive participle. The word “identical” is used because here and here only a “passive participle” exists even for intransitive verbs: омни ойдено omní óideno “I have left” (standard яс ошле iás oślé).

Past tense verbs formed using the l-participle conjugate slightly differently than in the standard. While singular verbs continue to agree with their subject in gender (masculine, feminine, or inanimate-formerly-neuter), if the subject is third person, an additional -й -i gets suffixed: я цидале iá cidále “I (masc) read”, он цидалей on cidálei “he read”; я цидала iá cidála “I (fem) read”, она цидалай oná cidálai “she read”. This does not occur in the dual or plural. This is derived from the 3sg clitic form of “be”. In Old Novegradian the present tense of “be” always had to be used in conjunction with the past tense. In the standard, this “be” fell out of use, but left this one trace in the North. This process does not extend to the future hypothetical (which also uses l-participles) in the Arhánjeiskei dialect, but has spread analogically in some others.

Another distinctive feature of Northern dialect verbs is the reshuffling of several directional prefixes used with verbs of motion to better align with the prepositional system. For instance, the standard prefix до- do-, indicating motion up to a destination, has been replaced by ко- ko- 1 , which does not exist as a prefix in other dialects: койсте kóiste “go/walk up to”. The prefix до-, in turn, has replaced standard под- pod- in the sense of “up to [a person]”: дойсте до ковуш dóiste do kovúś “walk up to someone”.

23.5.5.2 Nouns

The nominal system features a number of unusual endings, forms that have fallen out of use in standard Novegradian. It has also regularized some forms where multiple endings exist in the standard.

The neuter nominative singular ending has been generalized to -o in all cases. Neuter nouns that used to have -e -e now have -ё -io: морё mório “sea” (standard море móre), which now declines as a third declension noun. The nominative plural ending has also been generalized to an accented -á for all fourth declension nouns.

The locative case has been lost completely except in frozen adverbs, having been replaced by the accusative: по драгу po drágu “along the road” (standard по драгѣ po drágě).

The only fourth declension genitive singular ending is -у -u as in the third declension.

The dative/instrumental plural is -ама -ama for all nouns. This form is identical to the Common Slavic dual, though why this form has been kept and the plural -ам lost is unknown.

Sixth declension nouns with the suffix -en- appear with the suffix -ми -mi in the nominative singular: ими ími “name” (standard ймѣно jmě́no). This is equivalent to the Old Novegradian ending -мѣ -mě, which is no longer used.

The most unique feature is the prefixed /i/ many nouns gain due to a fallen yer in the first syllable. This prefix appears in all forms other than the nominative singular, accusative singular, and genitive plural. Without knowledge of the history of the language, however, it is not possible to predict where the prefix is needed. This prefix also appears in other parts of speech in some dialects, but in such cases it will appear in all forms (e.g., verbs such as изуати izuáti “call”, cf. standard зуати zuáti). Note that if the yer has fallen and there is no stress alteration at all (i.e., it never resurfaces as /o/ or /e/), no prefix is used: пеин pjín “I drink” (not **ипеин ipjín).

The second (ja) declension also has a very different appearance due to synharmony, which resulted in the fronting of most endings with back vowels.

| Singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| нига “book” | жемие “land” | ежеро “lake” | рот “mouth” | нокье “night” | ими “name” | |

| Nom | нига níga |

жемие źémie |

ежеро iéźero |

рот rót |

нокье nókje |

ими ími |

| Gen | ниги nígi |

жемеи źemjí |

ежеру iéźeru |

ирту irtú |

ногьи nogjí |

имену ímenu |

| A/L | нигу nígu |

жемеи źémji |

ежеро iéźero |

рот rót |

нокье nókje |

ими ími |

| D/I | нигой nígoi |

жемией źémiéi |

ежером iéźerom |

иртем irtém |

ногьюм nogjiúm |

именем ímenem |

| Part | нигох nígoh |

жемиех źémieh |

ежерох iéźeroh |

иртех irtéh |

нокьех nókjeh |

именех ímeneh |

| Lat | нигун nígun |

жемеин źémjin |

ежерон iéźeron |

иртен irtén |

нокьин nókjin |

именин ímenin |

| Voc | нигамо nígamo |

жемямо źémiamo |

ежеромо iéźeromo |

ротмо rótmo |

нокьмо nókjmo |

имимо ímimo |

| Plural | ||||||

| Nom | ниги nígi |

жемеи źémji |

ежера iźerá |

ирта irtá |

нокьие nókjie |

имена imená |

| Gen | ниг níg |

жем źem |

ежер iéźer |

рот rót |

нокьей nókjei |

имен ímen |

| A/L | ниги nígi |

жемеи źémji |

ежера iźerá |

ирта irtá |

нокьие nókjie |

имена imená |

| D/I | нигама nígama |

жемиема źémiema |

ежерама iéźerama |

иртама irtáma |

ногьама nogjáma |

именама ímenama |

| Part | нигоф nígof |

жемиеф źémief |

ежероф iéźerof |

иртеф irtéf |

нокьеф nókjef |

именеф ímenef |

| Lat | ниги nígi |

жемеи źémji |

ежери iéźeri |

ирти irtí |

нокьи nókji |

имени ímeni |

| Voc | нигимо nígimo |

жемеимо źémjimo |

ежерамо ieźerámo |

иртамо irtámo |

нокьиемо nókjiemo |

именамо imenámo |

In most spoken dialects, the possessive forms of kinship terms can appear as the complement of the verb “to be”, which normally requires the dative/instrumental case. In the Northern dialects, a trace of that instrumental is preserved by the insertion of на na “on” before the kinship term, since it cannot properly take the instrumental: Ше-и на другмо Śé-i na drúgmo “This is my friend”. Other sentences function as normal: Ше-и другем о Михи Śé-i drúgem o Míhi “This is Míha’s friend”. Compare this to the use of на before a noun in the instrumental in passive constructions in the standard.

23.5.5.3 Adjectives

Indefinite adjectives are more or less the same as in the standard, except that they may simplify in the nominative singular masculine and genitive plural when no ending is attached (nom.sg.masc новеградес novegrádes “Novegradian”, nom.sg.fem новеградеска novegrádeska). The dative/instrumental also has the plural ending -име -ime, contrasted with the -ама -ama of nouns.

Definite adjectives simplify in the nominative case, and the nom.sg.masc form has the ending -ой -oi instead of the usual -ей -ei: царвеной cárvenoi “red (masc.sg)”, царвена carvená, (царвене carvené), царвени carvení.

Northern dialects also make frequent use of adjectival possession, rarely seen in modern standard Novegradian. Adjectival possession is means of indicating possessive relationships, if the possessor is a person, by turning the possessor into an adjective. This is accomplished using the ending -оф -of (which becomes -ов- -ov- when another ending is added) for masculine nouns or names and -ин -in for feminine ones. This possessive adjective then takes indefinite endings agreeing with the noun being modified: татоф вуз tátof vúz “(my) father’s car”, Еванова жана Ievánova źaná “Ieváne’s wife”.

The ending -и is seen in the nominative case for all animate numerals: доваи dováji “two”, цетери céteri “four”, etc (standard доваин dóvajin, цетеро cétero). Modifiers such as numerals, determiners such as “all” or “both”, and all other ‘pronominal adjectives’ (adjectives following a more noun-like declension pattern) all use the dative/instrumental plural ending -ама.

23.5.5.4 Other Parts of Speech

The third person pronouns do not take the prefixed /n/ when following prepositions. Similarly, all prepositions like во vo “in” have lost their form containing /n/: на ево na ievó “on him/it” (standard на нем na ném). However, the /n/ is still seen in the third person forms of declining prepositions: ванму vanmú “in him/it”. The final /v/ added to some prepositions to break up hiatus has also been lost.

The conjunction да da is used instead of со so to connect multiple nouns in a single phrase. The nouns on both sides are in the same case: я да ти iá da tí “you and me”. Between clauses, on the other hand, it replaces the disjunction но no “but”: ойшал, да не дойшал oiśál, da ne doiśál “(He) left, but did not reach his destination” (standard ошле, но не дошле oślé, no ne doślé).

Northern dialects distinguish between unanalyzable and analyzable (phrasal) prepositions in that the latter may freely be postposed as well, and come after the noun they modify: вмести ме да те vmésti mé da té or ме да те вмести mé da té vmésti “between you and me”. However, this cannot be done with simple prepositions such as на “on”, пред “in front of”, or even compounded ones such as зенад “from above”, as these have no nominal componant.

23.6 The Siberian Dialects

23.6.1 Geographic Distribution

The Siberian dialects are the dominant spoken language in the trans-Ural portion of Novegrad, except in the far northwest around the lower portion of Ob River (Northern) and in various pockets along the Ural Mountains (Zavolotian). In many newer cities, as well as some of the largest Siberian cities, a dialect closer to the standard will be frequently heard.

23.6.2 History

The Siberian dialects are descended from an earlier form of the northern ones, spread by the Pomors who first penetrated the territory and explored the region’s great river systems. These first settlers were largely self-sufficient and isolated, giving them plenty of space and isolation for their dialect to develop.

After about one to two centuries, depending on the region, a new wave of settlers began moving into the territory from the west, especially once the major cities were connected by rail. These new settlers brought with them the more standardized language, though the first generations after them turned to a more mixed style of speech, which became the modern Siberian dialects.

23.6.3 Status

The Siberian dialects receive no official support, but are very important to the local Siberian Novegradian population, who tend to have a strong connection with their territory rather than the ‘European’ western half of Novegrad. It is often seen on shop signs and similar informal contexts, but in formal situations, everyone is expected to use the standard manner of speech.

23.6.4 Phonology

Phonologically, the Siberian dialects are very similar to the northern ones, except in the following respects:

Preservation of the Yat’: The yat’ /æ/ is preserved in stressed positions, just as in the standard.

Absence of /f/: The phoneme /f/ is not present in the Siberian dialects, as the standard influence has reinstituted /β/. However, unlike in the standard, /β/ is frequently seen word-finally and does not lenite to [w]. This has led to numerous incidents of hypercorrection, where /w/ derived from a former /u/ or /l/ have been hypercorrected to /β/. This is most noticeable in the past tense endings.

Stressed /o/ after /g/: The sequence /ˈgo/ in the standard dialect becomes /kuo/ in Siberia: куора kuóra “mountain” (standard гора góra), куород kuórod “city center” (standard городе górode).

Initial stress: Though far from universal, Siberian dialects show a much stronger tendency to stress the first syllable of a word, giving them a very distinctive rhythm. This also has the effect of making /wo/ and /o/ contrastive at the beginning of a word. Originally, [w] was inserted before initial stressed /o/. However, when the stress shift began in Siberian dialects, words that formerly began with unstressed /o/ that now had become stressed did not gain this on-glide. Note that derivational prefixes are usually unstressed.

23.6.5 Grammar

23.6.5.1 Verbs

Verbs are largely the same as in northern dialects, except that the future tense is marked by the particle буд búd (from бути “be”) instead of хекь hékj, or the standard буити + infinitive method is used. The northern past perfective construction has become limited to rural speech, though the 3rd person agreement in the past tense remains widespread.

In the past tense the suffixes used all contain /β/ instead of /l/. This originates from the original Siberian lenition of the old /l/ to /w/, which then became /β/ by hypercorrection. The dual past tense form has also been lost: цидав cídav, цидава cídava, цидаво cídavo, цидави cídavi. The loss of the dual ending (even when it was stressed) may be due to the reanalysis of the past tense forms as participles, which they had been in Proto-Slavic (see below).

Siberian dialects make extensive use of the suffix -ив- -iv- to form transformatives from adjective stems. This descends from an old iterative suffix that has lost productivity in most other dialects of Novegradian, but survives in a few fixed forms in the standard (e.g., the iterative буивати buiváti from бути búti “be”). Verbs with this suffix are A-conjugation in the imperative and I-conjugation in the perfective, and have the meaning “make X” in the active voice or “become X” in the middle voice:

- темней témnei “dark” → темнивати, темнивити témnivati, témniviti “darken, make dark”, темниватиш, темнивитиш témnivatiś, témnivitiś “darken, become twilight”

- ширей śírei “wide” → ширивати, ширивити śíriváti, śíriviti “widen”, шириватиш, ширивитиш śírivátiś, śírivitiś “spread out, cover territory”

- близей blízei “close” → близивати, близивити blízivati, blíziviti “cause to approach, bring about”, близивватиш, близивитиш blízivatiś, blízivitiś “approach (said of time, events, or weather)”

These forms often supplant existing causatives of the i- and ě-types common in standard Novegradian, such as standard темнѣти temně́ti for Siberian темниватиш témnivatiś “become dark”.

23.6.5.2 Nouns and Adjectives

The unusual genitive ending -u for fourth declension nouns has been replaced by the standard form -a, with sporadic application of -u following the same rules as in the standard. The one major exception is nouns which take the prefix и-, which seem to have become a new declension paradigm that always take their genitive in -u: ежера iéźera “of the lake”, but идну idnú “of the day”. The dative/instrumental plural -ама -ama remains, however, as does the merger of the accusative and locative cases. The nominative plural ending -и -i has been reintroduced for masculine and neuter nouns in most dialects, though not all (although a few go the other route and make -и the only allowable plural ending, never -а).

The sixth declension nominative ending, -ми -mi in the northern dialects, has become -ме -me in Siberia: име íme “name”.

Nouns that underwent a vowel shift regularize, generally with whatever vowel was in the nominative singular being generalized to all forms: мус mús “bridge”, мусти músti “bridges”.

The circumfix ending и-stem-а has actually gained more use in the Siberian dialects, having spread to a number of other one-syllable nouns, even if they never lose a vowel: вуз vúz “car”, plural ивуза ivuzá. This prefixed i- is seen in all forms but the nominative and accusative singular, and genitive plural. Exactly which nouns have acquired this prefix in their declension varies from region to region.

Adjectives have regained something closer to the standard, unreduced Novegradian endings: царвеней cárvenei, царвеная cárvenaia, (царвеное cárvenoie), царвении cárveniji. However, interestingly, the Siberian dialects have filled the gap in the Novegradian participle system by creating an active perfective participle, through reananlysis of the past tense forms: Ше-и дужой-то, овидивой ме вецераш Śé-i dúźoi-to, ovídivoi mé véceraś “That’s the person who saw me yesterday.” (standard Ше-и дужей-то, котрей мене овидѣле вецераш Śé-i duźéi-to, kótrei mené ovíděle véceraś).

The indefinite forms of adjectives are far more commonly used than in the standard, with the definite forms being relegated almost entirely to nominal and predicative roles. However, the masculine singular nominative ending -ей -ei, masculine singular accusative ending -ий -ij, and genitive plural ending -их -ih have displaced their indefinite counterparts, such that no adjectives ever take a zero ending.

23.6.5.3 Other Parts of Speech

These aspects remain largely the same as in Northern speech. However, the standard но no “but” has retaken its role from да da, though да is still used to link multiple nouns.

1) Derived from the preposition ко “to, towards”. ↑