1.1 Introduction

Novegradian (also called Novgorodian, from its name in Russian) is the official language of the Republic of Novegrad. With approximately 52 million native speakers, mostly in Novegrad and Russia, it ranks as the 23rd most widely-spoken language on Earth. It is the second most geographically widespread language of Europe, behind Russian, although it has very limited pickup as a second language outside of the Republic of Novegrad.

1.2 Novegrad

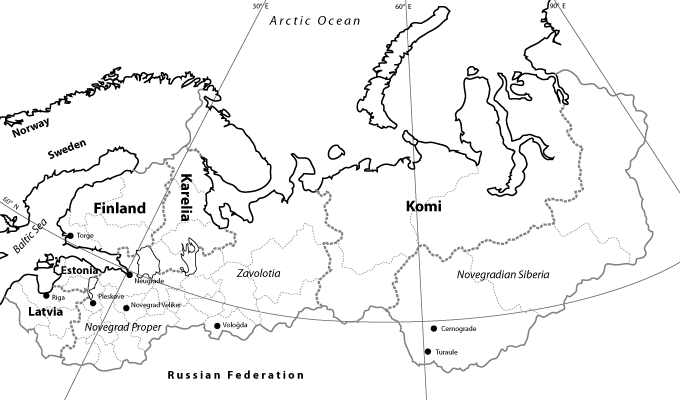

The Republic of Novegrad (Novegrádeskaia Respúblika, literally “Novegradian Republic”) spans much of northeastern Europe and the northwest of Asian Siberia, from the Baltic Sea to the Yenisei River. The cultural, economic, political, and historical center of the country is the area immediately around the capital city of Novegrad Velikei, one of the oldest cities of Eastern Europe.

Novegrad is a multiethnic nation, with five officially recognized nations aside from the Novegradians within its borders: the Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Karelians, and Komi. Within the territories of these peoples, local languages are spoken alongside Novegradian.

The rest of the country is typically divided into three main cultural and geographic regions. The westernmost area, up to roughly the Suda River, is often termed “Novegrad Proper” and is considered the heartland of the country. This is also the cradle of the Novegradian language. The rest of the European portion of Novegrad, up to the Ural Mountains, is known as the Zavolotia (Zavlácija), while the Asian portion is Novegradian Siberia (Śibíre). In these areas Novegradian was imposed as a colonial language, often supplanting local languages as the population of settlers grew and local peoples assimilated.

1.3 The Novegradian Language

Novegradian is part of Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. The Indo-European languages. The Indo-European languages span much of Europe and south Asia, and includes such languages as English, German, French, Greek, Armenian, Farsi, and Hindi.

The hypothetical ancestor of all the Indo-European languages, known as Proto-Indo-European, is generally believed to have been spoken around 4000 BC in the steppes of Ukraine and southwestern Russia between the Black and Caspian Seas, although both the date and location are subject to debate. As its speakers began to spread across Eurasia, the language began to disintegrate into a number of distinct dialects.

One of these daughter languages, known as pre-Proto-Slavic, is believed to have been spoken around the middle stretch of the Dnieper River by 1000 BC at the latest. Due to the many similarities between Slavic and the Baltic languages (a family including modern Latvian and Lithuanian), it is commonly held that the Slavic and Baltic languages had a shared ancestor, termed Proto-Balto-Slavic. Others suggest these similarities are the result of centuries of close contact between the inland Slavs and the peoples of the Baltic littoral.

Over the next few hundred years the early Slavs came in frequent contact with speakers of Germanic and Iranian languages as the Scythians, Sarmatians, and various east Germanic tribes moved into the area dominated by Slavic speakers. These contacts have had a significant impact on the Slavic languages, as can be seen in the large number of loanwords that entered the common lexicon at this point in time.

The true “Proto-Slavic” period begins with the massive Slavic expansion beginning in the 4th century AD. Over the relatively short span of several hundred years, the range of the Slavs expanded from their ancestral homeland coinciding roughly with modern Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland to take over most of Eastern Europe, from Novegrade Velikei in the north to Thessalonica in the south, and from the Oder in the west to the Don in the east. In the process Proto-Slavic displaced virtually all of the Celtic, Germanic, Balkan, and Finnic languages that had previously been spoken in this region.

The great expanse over which the language was now spoken, however, led to its own gradual disintegration into a number of dialects. There is evidence that as late as the 8th century virtually all of forms of Proto-Slavic were still mutually comprehensible, as the Old Church Slavonic translations of various Christian texts (based on the dialect of Thessalonica) was clearly understood by the Slavs of Bohemia and Moravia as well. The development of the four main groups of Slavic dialects marks the beginning of the period known as Common Slavic.

The four branches of Slavic languages that emerged out of the Common Slavic period are named for the four cardinal directions: North, South, East, and West Slavic.

South

East

- Old Church Slavonic

- Bulgarian

- Macedonian

West

- Slovene

- Serbian

- Croatian

- Bosnian

- Montenegrin

West

Lechitic

- Polish

- Kashubian

- Polabian

Czech-Slovak

- Czech

- Slovak

Sorbian

- Upper Sorbian

- Lower Sorbian

East

Russian

- Russian

Ruthenian

- Ukrainian

- Belarusian

- Rusyn

North

Novegradian

- Novegradian

The South Slavic languages were spoken throughout the Balkans, and would eventually give rise to modern Bulgarian, Macedonian, Serbo-Croatian (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin), and Slovene. These were split off from the rest of the Slavic languages relatively early by the invading ‘barbarian’ nations of central Asia that settled around the Carpathians.

The West Slavic languages were spoken in central Europe, roughly from Bohemia to the Vistula. These would develop into modern Czech, Slovak, Polish, and Upper and Lower Sorbian.

The East Slavic languages were used throughout the easternmost territory of the Slavs and most of the territory of Kievan Rus’. Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Rusyn can trace their origins to Old East Slavic.

The old North Slavic dialect was spoken in the northern provinces of Kievan Rus’, in the regions of Novgorod (Nóvegrade) and Pskov (Pleskóve). This would eventually become modern Novegradian.

As an Indo-European language, Novegradian naturally maintains many linguistic features typical of other Indo-European languages. Verbs have a complex fusional morphology indicating a number of tenses, aspects, and moods. Nouns similarly have a complex declensional system which incorporates three grammatical genders. Indo-European ablaut (vowel changes for grammatical or derivational purposes) are present, though no longer fully productive. It has nominative-accusative alignment, a neutral word order of subject-verb-object (SVO), and is primarily prepositional.

Among the Slavic languages, Novegradian is quite exceptional in a number of respects, testifying to its relatively early exit from Common Slavic. It never underwent certain changes seen in all other Slavic languages, such as the second regressive palatalization, while at the same time undergoing a number of unique developments not seen anywhere else, such as its reorganization of the inherited Slavic declensional patterns. These issues will be dealt with in more detail in section 24, “History Phonology and Morphology”.

Due to its northern location on the Slavic periphery, Novegradian also had extensive contact and influence from the Uralic languages, a non-Indo-European family spanning from Finland and Lapland to central Siberia. These contacts have had a profound impact on Novegradian morphology, syntax, and of course its lexicon.

1.4 History of Novegradian

Originally Novegradian and Russian were considered the same language, being little more than regional variants spoken among the peasantry in the kingdom of Kievan Rus’. However, this was not necessarily an accurate characterization, as the two languages were already displaying very different features. As Kievan Rus’ fractured, the Novegradians distanced themselves from the Russians of Kiev and later Moscow, and the Novegradian language began to develop its distinct identity.

The earliest attestations of a distinct Novegradian dialect date to the 11th century AD. It was most prominently displayed in the thousands of short letters and notes carved on birch bark dating from between the 11th and 14th centuries, which were reasonably well preserved due to the marshy, anoxic soil around much of Novegrad Velikei. Analysis of these and other documents suggests basic literacy in Novegradian cities at the quite was surprisingly high and was present in virtually all classes of society. This was not, however, literacy in the way it is understood nowadays; these people seem to have known the Cyrillic alphabet quite well, but knowledge of formal Church Slavonic (the written standard throughout Rus’) was much rarer. As a result, we have a large number of these birchbark documents written the only way these people knew how to write—exactly as they spoke.

The standard language of the educated throughout most of Rus’ was Old Church Slavonic, a South Slavic language that spread alongside Orthodox Christianity among the elite. Its influence would be felt on Russian well into the 18th century, with Church Slavonic vocabulary composing a large portion of the lexicon. In Novegrad, however, the influence of Old Church Slavonic was much smaller and rather limited outside the realm of religious vocabulary; the few surviving texts from Novegrad composed in ‘Old Church Slavonic’ contain a large number of misspellings based on local pronunciations and local vocabulary absent from the Old Church Slavonic of the rest of Rus’.

Up through roughly the late 14th century the main external influences on Novegradian were Germanic and Finnic. At this point the gradually-expanding territory of Novegrad included a large number of Finnic peoples, most notably the Karelians, as well as Novegradians in close proximity. Early on many Novegradians and Karelians were bilingual in each other’s languages, allowing many typically Finnic grammatical features and vocabulary to be incorporated into Novegradian. Most of the Karelians south of the Svir River were assimilated into Novegradian culture by the late 15th century.

During this same time period, extensive contact with a number of Germanic nations took place mostly through trade and warfare. Novegrad Velikei hosted one of the largest marketplaces of the Hanseatic League, a merchant organization based out of the German city of Lübeck (in Novegradian, Lúwce). The Novegradians had a less friendly relationship with the Swedes and Teutonic Knights, who they were frequently at war with. The Germanic influence was not nearly as direct as the Finnic influence, but nevertheless resulted in quite a few terms relating to trade, government, and warfare entering common usage.

The Mongol invasions and the time of the Tatar yoke in Rus’, lasting from the mid 13th to the late 15th centuries, had much less of a linguistic impact on Novegradian as it did on Russian, although it was nevertheless felt. Novegrad managed to remain independent of the Mongols, though many terms related primarily to commerce and law filtered down via Russian.

The 15th through 17th centuries marked a new period of Uralic influence, this time primarily from the Permic languages, such as Komi. As the Novegradians expanded further and further into the Zavolotia and new trade routes developed to Europe through the White Sea and overland to the Middle East and China through Siberia, the population of the Novegradian East grew rapidly.

Western European influences began to appear starting in the 17th century and really took off in the 18th as contact between Eastern and Western Europe at last started to become reestablished after hundreds of years of separation. French became the language of the courts, German of the military, and Dutch of the merchant marine. The Novegradian language was flooded with westernisms as French high culture became fashionable. However, during this same time, interest in actually codifying the Novegradian language first began to appear.

In the 19th century, this trend underwent a sharp reversion. Novegradian nationalism and pan-Slavism swept through the country, and purists sought to purge the language of Western elements. Latinate vocabulary and ‘internationalisms’ were replaced by native coinages, many of which did succeed in becoming entrenched. Russian began to replace French as the language of prestige, aided of course by the temporary integration of Novegrad into the Russian Empire.

The new sense of Novegradian nationalism and shared identity also manifested itself in the development of the first attempts at complete grammars and dictionaries. One, Vladímire Sisóline’s Грамматіка Новеградескаго Іизыка Grammatika Novegradeskago Iizyka, would become the standard up until the mid-20th century with few changes other than spelling. It was, however, heavily influenced by Russian and poorly represented the actual state of spoken language.

Russian influence continued to grow well into the 20th century, when Novegrad, once again nominally independent, became a close associate of the Soviet Union and later a member of the Warsaw Pact. As the political regime swayed between nationalism and sovietization, Russian went through varying degrees of official promotion to the detriment of Novegradian; to the present day nearly all Novegradians over 50 years of age can speak Russian with varying degrees of proficiency. However, during this same period, the Novegradians once again became more receptive to ‘internationalisms’, especially with regards to technology.

The 1960s saw the first attempts at revising the traditional russified model of the Novegradian standard. For the previous two hundreed years, Novegradian suffered a sort of identity crisis, with both the literary and political elite encouraging a much more “Slavic” (i.e., Russian) grammar while downplaying many of the more divergent aspects of the language. While still not fully representative of many Uralic influences, among other features, it represents a significant step towards establishing Novegradian as a language equally worthy of respect and prestige as Russian.

Since the fall of the Eastern bloc in 1991, the single greatest influence on Novegradian has been English, the new international language of technology and business. More and more Novegradians are learning English, and English loans have penetrated virtually every sphere of life. Reactions to this, however, have been mixed, with growing alarm at its sheer pervasiveness.

There continues to be a prominent diglossia in Novegrad between the standard language and the spoken language. However, the democratization of expression in recent years has led to an increase of awareness and acceptance of many aspects of spoken Novegradian and of its regional dialects. In fact, today there exist three different standards for the formal spoken language: one used in Finland, one in Latvia, and one throughout the rest of Novegrad. These three standards only have minor differences, but hearken back to the formative days of the language when the Novegradians wrote as they spoke, not according to an imposed guideline.

1.5 Introduction to this Grammar

This reference grammar seeks to outline the basic principles of Standard Novegradian as is taught in schools in Novegrad Velikei and is expected to be used in semiformal and formal circumstances throughout the country. This will be followed by a discussion of other forms of Novegradian—aspects of the spoken language that are not codified in descriptions of the standard written language in Chapter 22, and both the standardized and non-standardized dialects of Novegradian in Chapter 23. However, references to the spoken language will be made throughout this text when appropriate.

This grammar begins with a description of the phonology and writing system of the language in order to provide a foundation for pronunciation and reading throughout the rest of the text. From here, morphology and word formation will be examined, with emphasis on structure rather than meaning. All of this information will then be combined in the chapters on syntax, which will detail the actual usage of all of these forms.

At the end of this grammar are a number of appendices explaining other features (mostly lexical) that did not fit anywhere else. Chapter 24 contains a detailed historical account of the development of modern Novegradian from a technical perspective, detailing the emergence of Novegradian phonology and morphology from Common Slavic.

Standard Novegradian orthography using the Cyrillic alphabet will be employed throughout this text. For ease and clarity, however, transliterations will always be provided in italics. English translations always appear in double quotation marks: новеградескей лизике novegrádeskei lizíke “the Novegradian language”. Details on the orthography and transliteration scheme are provided in Chapter 3.

Phonetic transcriptions will appear in [square brackets], while phonemic transcription appear in /forward slashes/, as per linguistic convention. All phonological transcriptions use the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Once more of the morphology has been introduced and usage is being examined more in depth, interlinear glosses will be used alongside transcriptions and translations. These provide a morpheme-by-morpheme breakdown of a given Novegradian word or phrase. Multiple morphemes are separated by hyphens, while a morpheme conveying multiple meanings at once will have those meanings separated by a period. Non-lexical morphemes appear in smallcaps. For instance, Novegradian uses a single morpheme to mark a noun as being in the accusative case and singular in number, so the accusative singular of the word “book” would be indicated book-acc.sg. Null morphemes are indicated with Ø; however, this is usually only done to draw attention to the fact that a particular morpheme has zero surface realization.

Hypothetical word forms, in particular reconstructed forms of a proto-language, will be preceded by a single *asterisk. Non-existent forms, used for instance to indicate an exception to a pattern, will be preceded by **two asterisks.