3.1 History of Written Alashian

Throughout its attested history, Alashian has been written in quite a few different scripts.

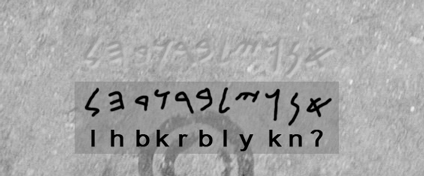

The earliest extant texts that with little doubt represent archaic Alashian were written using the Phoenician alphabet, brought to the island of Cyprus by Phoenician tradesmen from the Levant. Most of these texts are quite short or fragmented, consisting primarily of names, votives, inventories, and claims of ownership. Since the grammar of such sort texts is limited, we rely first and foremost on various phonological pecularities to identify these texts as Alashian, such as the confusion of the Phoenician glyphs for /h/ and /ʕ/, which merged as /h/ early on in Alashian history.

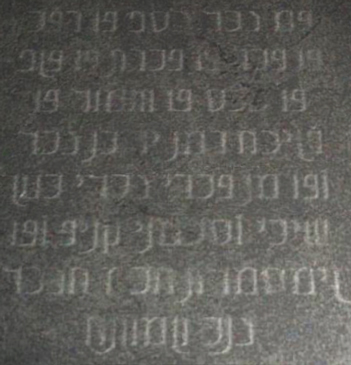

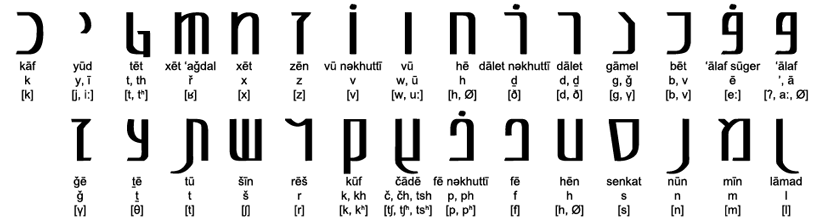

This script was later supplanted by an Aramaic-derived script. This came to be known as the “Old Alashian” alphabet, which remained in widespread use until the first few centuries AD, although it continued to be used for liturgical purposes much later. Like other Semitic scripts, it consisted of a consonantal alphabet with long vowels marked by certain matres lectionis (consonant letters that could also serve as vowels), while short vowels were unmarked.

The Aramaic alphabet was expanded with additional letters which are typically attributed to the Cypriot syllabary previously used on the island by the Greeks and Etiocypriots. However, even with these additions, the Alashian script did not accurately reflect the Alashian sound system, as many letters had multiple values and often a single sound could be written with multiple letters. Proper usage simply required memorization.

Problems with spelling and pronunciation were partially rectified around the 7th century AD (once the script had been reduced mostly to a liturgical function) with the introduction of a number of diacritics. The nəkhəthā, or 'dot', was added to certain consonants to distinguish their multiple phonetic values, and a system of vowel diacritics was introduced to ensure accurate pronunciation. There was, however, no reduction in the redundant letters.

By the 4th century AD the Alashian alphabet had been more or less supplanted by the Greek script for most daily functions. Spellings were not standardized, so many different schemes emerged for representing Alashian sounds that the Greek script could not easily encode. No single standard spelling would emerge until the 19th century.

Although never widely used, Alashian written in Arabic-based script is attested in a few texts from the 8th through 17th centuries and appears to have been used by members of the Muslim community on Cyprus.

3.2 Modern Alashian Alphabet

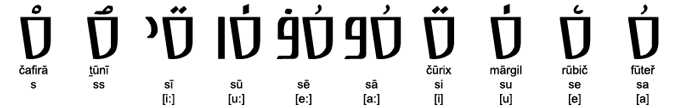

Alashian nowadays is almost always written using a modified version of the Greek alphabet, a spelling system that was only actually standardized in the 1890s, in the wake of a number of nationalist revivals in the Balkans and Near East. It makes use of diacritics (the overline) and digraphs to represent sounds not present in Greek, and for the most part is a far better fit for the language than any other script that had previously been used, although it is far from perfect.

The alphabet consists of the following 29 letters:

| Letter | IPA | Translit. |

Name

(IPA) |

Name

(Translit.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Α α | a, ə | a, ə | ˈʔaːlaf | 'ālaf |

| Β β | b | b | ˈbeːt | bēt |

| Β̄ в̄ | v | v | ˈveːt | vēt |

| Γ γ | g | g | ˈgaːm | gām |

| Γ̄ γ̄ | γ | ǧ | ˈγaːm | ğām |

| Δ δ | d | d | ˈdaːl | dāl |

| Δ̄ δ̄ | ð | ḏ | ˈðaːl | ḏāl |

| Ε ε | e | e | ˈʔeːt | 'ēt |

| ΕΙ ει | iː | ī | ˈjuːd maθˈnuː | yūd maṯnū |

| Ζ ζ | z | z | ˈzeːd | zēd |

| Η η | h, eː | h, ē | ˈʔeːt maθˈnuː | 'ēt maṯnuː |

| Θ θ | θ | ṯ | ˈθeːt | ṯēt |

| Ι ι | j, i | y, i | ˈjuːd | yūd |

| Κ κ | k, kʰ | k, kh | ˈkaːf | kāf |

| Λ λ | l | l | ˈlaːn | lān |

| Μ μ | m | m | ˈmiːn | mīn |

| Ν ν | n | n | ˈnuːn | nūn |

| ΟΥ ου | uː | ū | ˈvuː maθˈnuː | vū maṯnū |

| Π π | p, pʰ | p, ph | ˈpiːt | pīt |

| Ρ ρ | r | r | ˈreːʃ | rēš |

| Ρ̄ ρ̄ | ʁ | ř | ˈʁeː | řē |

| Σ σ ς | s | s | ˈsiːt | sīt |

| Σ̄ σ̄ ς̄ | ʃ | š | ˈʃiːt | šīt |

| Τ τ | t, tʰ | t, th | ˈtuː | tū |

| ΤΖ τζ | tʃ, tʃʰ | č, čh | ˈtʃaːt | čāt |

| Υ υ | w, u | w, u | ˈvuː | vū |

| Φ φ | f | f | ˈfeː | fē |

| Χ χ | x | x | ˈxeː | xē |

| Ω ω | aː | ā | ˈaːlaf maθˈnuː | 'ālaf maṯnū |

The names of the letters reflect a mixed Semitic/Greek origin. Most letter names reflect the names of their original equivalents in the Old Alashian script, though reduced to a single syllable (except 'ālaf) and with a long vowel generalized to all letter names. Syllable codas are for the most part historical, but a number appear to be almost random; some, such as -t and -n, have been widely generalized far beyond their etymological distribution. The word maṯnū means “doubled”, and is used to indicate the long vowels.

3.3 Spelling and Orthographic Conventions

Although this script comes the closest to having a one-to-one phoneme correspondence, it nevertheless has a number of quirks and shortcomings.

3.3.1 Digraphs

Alashian makes use of three digraphs which are considered letters in their own right: ει ου τζ. The first two represent the long vowels /iː/ and /uː/, the latter the affricate /tʃ/. The first element of ου is the Greek letter omikron, which is not used anywhere in Alashian except in this particular digraph (a consequence of how the Greek script as used for the Greek language marks /u/).

Alashian's two diphthongs are also written as digraphs, although they are not considered separate letters: ιη ie, υω uo, spelled as though they were iē and uā.

Since these letters consist of two components, they have three cases, unlike all other letters: majuscule ΕΙ ΟΥ ΤΖ, minuscule ει ου τζ, and title Ει Ου Τζ. Majuscule is used only in all-caps text, with title case being the appropriate form to use at the start of a sentence or otherwise whenever the first letter of a word is intended to be capitalized but the rest are not.

3.3.2 Schwa

The vowel /ə/ is not distinguished from short /a/ orthographically; both are written as α. In this grammar, however, the a/ə contrast will always be indicated in romanization.

3.3.3 Stress Marking

Alashian consistently marks stress using an acute accent over the stressed vowel: ά έ ί ύ ώ. On digraphs, the second letter takes the accent: εί ού.

Accented majuscule letters exist as well, formed by shifting the accent mark to the left of the letter: Ά Έ Ί Ύ Ώ. However, stress is usually not marked on majuscule letters unless the letter is the first character in a word. In all-caps text, for instance, there will generally be very few stress marks written.

3.3.4 Semivowels

The semivowels /w j h/ all share letters with a vowel: η marks both /eː/ and /h/, ι marks both /i/ and /j/, and υ marks both /w/ and /u/. For the most part, however, this is not a problem, as the vocalic pronunciation can be assumed when the letter appears between two consonants and the consonantal pronunciation elsewhere.

Potential confusion only arises in two cases:

- If a glottal stop is present. The glottal stop is not indicated orthographically (see next section), so based on spelling alone it is impossible to predict whether a sequence like ηα represents ha or ē'a. In this grammar, this will always be disambiguated by the transliteration.

- If multiple semivowel letters appear in a sequence. This is especially obvious in certain forms of the verb 'to be'.

3.3.5 The Glottal Stop

The glottal stop /ʔ/ is never indicated orthographically. In many cases, however, it can be implied, such as when a vowel letter appears word-initially (since word-initial vowels must be preceded by /ʔ/), or if two vowels appear in a row (e.g., αε must be /aʔe/, since /ae/ cannot occur).

3.3.6 Gemination and Aspiration

Gemination is indicated by simply doubling a glyph: ττ tt, σσ ss, μμ mm. The geminate /tʃtʃ/, however, is spelled τζζ čč rather than as τζτζ.

The aspirated consonants /pʰ tʰ kʰ tʃʰ/, however, are also indicated by doubling the glyph: ππ ph, ττ th, κκ kh, τζζ čh, at least when intervocal; elsewhere the single consonants π τ κ τζ σ are used, since the aspiration is not present. It is thus impossible to tell whether these particular consonants are geminated or aspirated based purely on spelling, or whether a given π τ κ τζ σ in non-intervocalic position represents an underlying aspirated or unaspirated consonant.

The aspirate /tsʰ/ has a similar problem. It is spelled τσ tsh, which is indistinguishable from the cluster τσ ts.

3.3.7 Marking of Subphonemic Features

Alashian orthography consistently marks the sound [c] (an allophone of /j/ after a voiceless consonant and before a stressed vowel) as κι, even though this contrast is subphonemic and completely predictable. Thus the feminine singular form of the adjective αλασεί 'alasī “Alashian” is αλασκιώ 'alaskyā, even though the word is phonemically /ʔalasjaː/.

Nasal assimilation with /r/ (where /mr/ and /nr/ become [br] and [dr]) is also consistently shown in Alashian orthography, despite being an automatic process.

3.3.8 Miscellaneous Irregularities

The Alashian definite article is marked with a prefix which can take various forms. One of the most common ones is ha-. However, here and here only, the /h/ is never indicated, and the prefix is spelled α-. Initial /h/ elsewhere in Alashian is always explicitly marked with η.

Another common clitic prefix is the conjunction “and”, ve- (as well as several other variants). It is always spelled with as υε-, with the letter for /w/, never as в̄ε-.