1.1 Introduction

Očets (also known as Hočets Seie “Očets Tongue” or Šteie “Our Language”, or in Novegradian очецескей лизике očéceskei lizíke) is the language of the Očets people of northwestern Siberia, primarily in the Oraltouskáia Óblosti of the Republic of Novegrad. In older texts they are sometimes know as Očaks (Novegradian очаке óčake, plural очаци óčaci). There are approximately 40,000 speakers, mostly in the countryside, but there are a number of sizable cities with large Očets minorities.

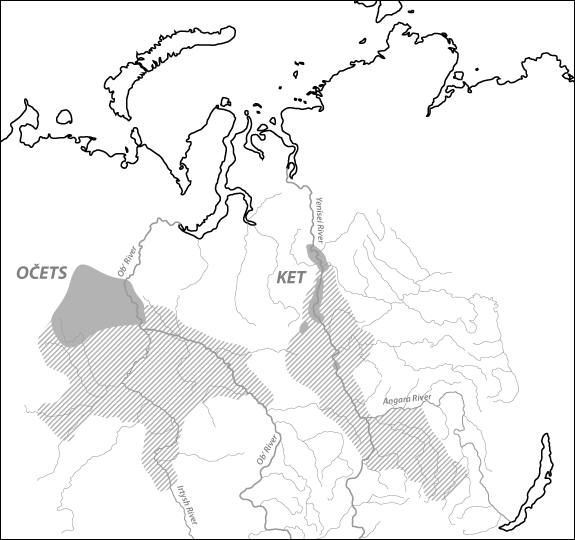

Očets is a member of the Ob-Yeniseian language family, a small group of languages spoken or once spoken along the Ob’ and Yenisei Rivers in northern Siberia. Its only surviving relative is Ket, spoken by several hundred people in the northernmost stretches of the Yenisei.

The Očets people appear to have lived in the same general area for at least the last thousand years, and so their language has been heavily influenced by other languages of western Siberia and the Ural region, such as Komi, Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, and Tatar, and of course Novegradian since the 17th century. For most of its history, the language was unwritten. There are scant examples of written Očets since the early 19th century, but a written standard did not emerge until 1937, based on the Novegradian Cyrillic alphabet and the numerous other orthographies developed for Siberian languages around the same time.

There are no monolingual Očets speakers today except for some children below school age, although many older speakers may not know Novegradian; they instead have learned Komi, once the dominant lingua franca of the countryside.

Most of the ethnic Očets speak both Očets and Novegradian. Most learned Očets at home as their mother tongue and learned Novegradian in schools. For most of the 20th century the total number of speakers has been declining, although due to recent renewed interest and activism the rate of decline has been reduced drastically over the last decade. Currently there are three Očets newspapers in publication, as well as two television stations (one of them part time) and two radio stations. It is not currently taught in schools except optionally in a few elementary schools and in several universities with specialties in Uralic and Siberian languages.

1.2 The Ob-Yeniseian Languages

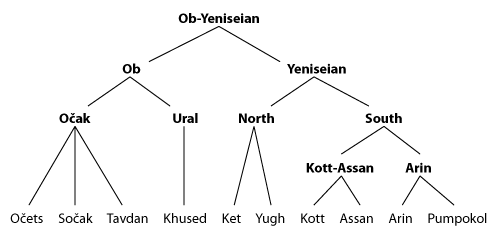

The Ob-Yeniseian family is divided into two branches, Ob and Yeniseian, named for the river systems along which speakers lived.

The Ob branch is by far the largest in terms of total speakers. Očets is the only living representative, although several other now-extinct languages are known from wordlists and tax records, though relatively little is known about them. These include Sočak (extinct by 1980) and “Tavdan” (extinct in the 17th century), which appear to be closely related to Očets, and Khused (extinct in the late 19th century).

The Yeniseian branch can be subdivided into Northern and Southern branches. The southern branch is extinct, and included Assan and Arin (both extinct in the 18th century) and Kott (extinct in the 19th). The northern branch consists of Ket and Yugh; the former is still in use by several hundred speakers, the latter went extinct for all practical purposes in the 1990s, with only a handful of non-fluent speakers remaining. Another language, Pumpokol, is attested only in short word lists, and its classification is not clear.

Očets and Ket are therefore the sole surviving Ob-Yeniseian languages. Prospects for Očets in the near future seem moderate to good, with a sizeable speaker base and active community culture. Ket unfortunately appears to be moribund, with communities switching to Novegradian and virtually nonexistent use of the language among children, despite recent efforts to offer primary education in the language.

The Ob-Yeniseian languages are typologically very unique for western Siberia. They feature a heavily prefixing morphology, varying degrees of nominal incorporation, and in the case of Ket, an unusual tonal system. However, centuries if not milennia of contact with other local Uralic, Turkic, and later Indo-European languages have left a clear mark on the family, both lexically and grammatically. The strange typology has led researchers over the years to connect Ob-Yeniseian with numerous other languages families. None of these attempts have met with much support until recently, as a link with the Na-Déné languages of North America (including Tlingit, Hupa, Apache, and Navajo, among many others) appears to be gaining increasing popularity. This so-called “Déné-Yeniseian hypothesis”, if true, would mark the first established link between language families of the New and Old Worlds.

The relationship between the various Ob-Yeniseian languages can be most easily seen in cognate vocabulary. For instance, the numbers 1-10 in several of the Ob-Yeniseian languages are reproduced below. Not all of the forms below are cognate, however; in particular, the numbers 8 and 9 come from a variety of sources, and cannot be reliably reconstructed in Proto-Ob-Yeniseian (which is shown in the last column).

Parentheses indicate forms not descended from the corresponding Proto-Ob-Yeniseian root. This generally indicates either borrowing from another language, or a complex form based on native structures (e.g., Ket “two from ten”, Kott “five and three”, both meaning “eight”).

| Očets | Khused | Ket | Kott | POY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | quus | huuda | qoʔk | hūča | *quu- |

| 2 | kyn | kuna | ȳn | īna | *kin- |

| 3 | doŋ | ðuŋka | doʔŋ | tōŋa | *don’- |

| 4 | šees | šeida | sīk | šēgä | *sī- |

| 5 | keis | haida | qāk | xēgä | *qai- |

| 6 | kaats | kašda | ā | (xelūča) | *kax- |

| 7 | haun | (čeda) | oʔn | (xelīna) | *on- |

| 8 | (wous) | (saega) | (ýnam bənsaŋ qō) | (xaltōŋa) | ? |

| 9 | (ǰeut) | (toga) | (qúsam bənsaŋ qō) | (čumuāga) | ? |

| 10 | iaus | dzauda | qō | hāga | *gau- |

1.3 History

Due to the paucity of written records, it is difficult to trace the prehistory of the Očets people. Most current models of population movements are based on archeological and linguistic evidence (the latter mostly being in the form of toponyms and hydronyms containing Ob-Yeniseian elements). Other techniques, such as genetic analysis and comparative mythology, are still in their infancy when it comes to this region.

It is generally held that the ancestors of the Ob and Yeniseian peoples, arrived in central Siberia from further east (which appears to be reflected in some traditional stories of the Očets people as well).

Around the fifth century BC the Ob-Yeniseian homeland appears to have been to the east of Lake Baikal, in the Angara river basin and possibly along the lakeshore itself. This is were the oldest layer of Ob-Yeniseian toponyms appears to originate from. Ob-Yeniseian loans in some of the nearby South Siberian Turkic languages suggest a relatively active system of trade emerging along the upper Yenisei river.

The Ob-Yeniseian people were skilled boatsmen, and their range of influence quickly spread through the Yenisei basin and into parts of the Ob’ basin. At this stage they were still largely nomadic, however, with frequent movements up and down river as the seasons changed.

Later in the first millennium massive nomadic movements across southern Siberia resulted in the northward displacement of most of the Ob-Yeniseian tribes, as well as a permanent separation between the tribes living along the Yenisei and Angara rivers and those that had resettled in the Ob’-Irtysh river system further west.

Ob and Yeniseian cultures began to increasingly diverge over the following centuries. The Yeniseian peoples that are best documented appear to have remained highly nomadic; in fact, they appear to have never even acquired a tradition of animal husbandry, relying entirely on hunting, fishing, and trade for food up until the 20th century; in this regard they are unique for the region. The southern Yeniseian peoples, however, did raise animals; however, very little record of them remains.

The Ob cultures, being further west, ended up in more direct contact with various Turkic-speaking and Uralic-speaking peoples, as well as the Indo-Iranians who once dominated the central Asian steppe. While still largely nomadic, they did practice traditional animal husbandry.

Permanent settlements did not appear among the Očets until after the start of Slavic colonization in the region, which also brought along with it Orthodox Christianity, now the predominant religion of the Očets. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the process of settlement rapidly sped up; at present there are very few Očets people who still live a nomadic lifestyle.

Over the last few centuries the territory in which Ob languages were spoken has rapidly contracted. Očets territory is now mostly concentrated between the middle reaches of the Ob’ River and the Ural mountains. Much of this territory is relatively sparsely-populated, leading to great distances between some Očets-speaking villages. Within this region there are three main clusters of speakers: in the east along the Ob’ River, in the north along the Urals, and in the southwest, a more heavily urbanized region where significant Očets-speaking populations coexist with Novegradian speakers in the cities.

1.4 The Name “Očets”

The name “Očets”, as well as the dated “Očak”, appears to originate from 17th-century dialectical Očets Hos(d) Čeidəz “People of the Ob”, paralleling the term “Ostyak” (of Khanty origin) used by the Novegradians and Russians to refer to many different peoples of Siberia.

It was not originally an autonym, but rather a term used by the Novegradians to refer to the Očets. It was subsequently borrowed back into Očets as the Novegradian language started to dominate the region, and to this day they refer to themselves as һочец hočets or һочак hočak. The original Očets name for their own people and language is not known. The term шадден šadden (lit. “our people”) is often seen in poetry and formal contexts, but it is impossible to know whether this once served as the primary autonym.

1.5 Introduction to this Grammar

This reference grammar seeks to outline the structure of standard Očets, which serves as the standard form of the spoken and written language in most contexts. It will also provide a brief survey of dialectical forms, and will cite non-standard forms when it is informative to do so. Note that standard Očets seeks to use native terms and structures whenever possible; in practice, however, strong Slavic influence can be seen in both structure and vocabulary.

This grammar begins with a description of Očets phonology and morphophonemics, which can be quite complicated. This is followed by a discussion of the Očets version of the Cyrillic alphabet, which is used in all written contexts, and so will be used here as well (alongside forms transliterated into the Latin alphabet).

The following several chapters are dedicated to morphology, separated by parts of speech. Emphais here is placed on structure and formation, not on meaning; use of forms is discussed later. Due to Očets’s complex morphophonemics, a special notation denoting underlying forms (with all vowel harmony and sandhi operations stripped off) will be introduced in these sections. Afterwards come several sections entirely dedicated to usage and syntax.

At the end of the grammar are several chapters dedicated to various other aspects of Očets, in particular colloquial usage and Novegradian contact influence/sociolects, Očets dialect groups, and the historical development of Očets phonology and morphology.

Phonetic transcriptions will appear in [square brackets], while phonemic transcription appear in /forward slashes/, as per linguistic convention. All phonological transcriptions use the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Once more of the morphology has been introduced and usage is being examined more in depth, interlinear glosses will be used alongside transcriptions and translations. These provide a morpheme-by-morpheme breakdown of a given Očets word or phrase. Multiple morphemes are separated by hyphens, while a morpheme conveying multiple meanings at once will have those meanings separated by a period. Non-lexical morphemes appear in smallcaps. For instance, the objective plural of the word “book” would be indicated book-pl-obj. Null morphemes are indicated with Ø; however, this is usually only done to draw attention to the fact that a particular morpheme has zero surface realization.

Hypothetical word forms, in particular reconstructed forms of a proto-language, will be preceded by a single *asterisk. Non-existent forms, used for instance to indicate an exception to a pattern, will be preceded by **two asterisks.